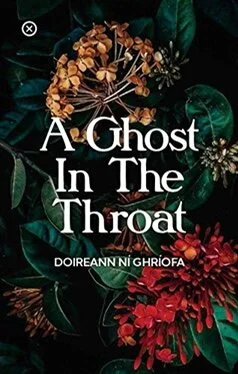

Sometimes writing has a kind of talismanic force drawing us into the past so that we feel enlivened and profoundly connected to the sensibility found in the text. “A Ghost in the Throat” is a book dedicated to such an experience. It's part memoir, part exercise in fiction and part process of translation. Doireann Ni Ghriofa meditates upon the life and writing of Eibhlin Dubh, an 18th century poet and member of the Irish gentry. After her husband's murder, Dubh composed the ‘Caoineadh Airt Ui Laoghaire' which is a long poem or dirge that is a visceral cry for this agonising loss which still feels painfully real centuries later. Ghriofa connects to this voice and it fills her imagination as she goes about her days caring for her children. She sets out to translate the poem from the Gaelic into English but is also drawn into researching and recreating what can be traced of Eibhlin Dubh's life since little is known about what happened to her following her husband Art's murder except through the recorded history of her children and their progeny. The caoineadh wasn't originally written down but orally passed along over time until it was eventually set to paper so the text is also imbued with the lives of all who've spoken it. Ghriofa meaningfully describes how this makes it a uniquely “female text” and how the state of motherhood physically connects her to a wider sense of women's history. It's extremely moving how Ghriofa describes the way Dubh becomes such a strong presence in her life and how that connection is transformative.

Ghriofa is a poet so there is a lyricism to her writing which reveals the deeper meaning and beauty of everyday tasks even while acknowledging that reality can often be habitual and mundane. Her intense desire to research the poem and Dubh's life prompts her to continue doing so even when the demands of motherhood mean her time must be parsed out in carefully planned minutes. She writes that “This is the life I have made for myself, always striving for something beyond my grasp, while hauling implausibly complex armfuls.” Yet there's a nobility to her efforts which show how this is the way in which life is meaningfully spent. The fact that so little was recorded about Dubh's life says something about the way history placed less importance on the lives of women. Ghriofa's task of tracing the barest of clues and imaginatively filling in the blanks is both an act of commemoration and a reclaiming of this female lineage. She acknowledges that “We may imagine that we can imagine the past, but this is an impossibility.” So the narrative she creates is necessarily a fiction and imbued with her own sensibility, but it takes on its own power and truth. This book is startlingly original in the way it describes how great literature can become a living presence in our lives and I loved the expansive power of Ghriofa's prose.