If your house was on fire and you could only grab one book to save what would it be? Okay, unfair question. I don’t think I could answer it either. I’d probably be found by the firemen stumbling out of my apartment building coughing smoke, arms loaded with charred books and begging them to go in to save the rest. Books don't just contain their own stories, but the story of our relationship to them. I really value so many of my books, but if I were asked to pick out my favourites then these would be some at the top of the list.

This special shortened bookshelf houses most of my most treasured books. All of them are signed and many are special limited editions and many have sentimental value.

The Color Purple was the first book I ever had signed by an author. When stopping in a bookshop in Boston one day I noticed an ad for an Alice Walker reading at the Boston Public Library happening right now. I quickly bought this copy and rushed over catching Walker right before the end of her signing.

The signed Eugene Ionesco was one of the first expensive books I bought when I was earning enough to be able to afford it as he is one of my favourite authors.

The Lord John Ten anthology is signed by many prominent authors including Ray Bradbury, Raymond Carver, Derek Walcott and many others.

I bought the signed copy of Austerlitz only a couple weeks before W.G.Sebald’s tragic death. Since it was published so shortly before he died very few were signed and it’s now apparently worth hundreds of pounds.

Most of the hardback novels I’ve kept have been ones I’ve been able to get signed by the author in person when attending readings – many at the Royal Festival Hall in London. I have fond memories attached to the times I bought each of them.

Michael Downing was my first creative writing teacher when I was an undergraduate at Wheelock College in Boston. He was a tremendous inspiration and this fine novel which is a tribute to the importance of grammar was published while I was studying with him.

When I first arrived in London I noticed the Waterstones near Trafalgar Square was hosting a reading by Joseph Heller. I rushed over and listened to him speak as well as getting him to sign this copy of his novel Something Happened.

Jean Rhys is one of my favourite writers and this copy of her story My Day is part of a limited lettered edition of only 26 books.

Edmund White is a phenomenal writer and an incredibly generous human being. I’m very lucky to be able to call him a friend. His historical novel Fanny: A Fiction is one of my favourite books by him. It's a tale of two very different women from history that formed an unlikely friendship and who tried to establish a utopian community in America.

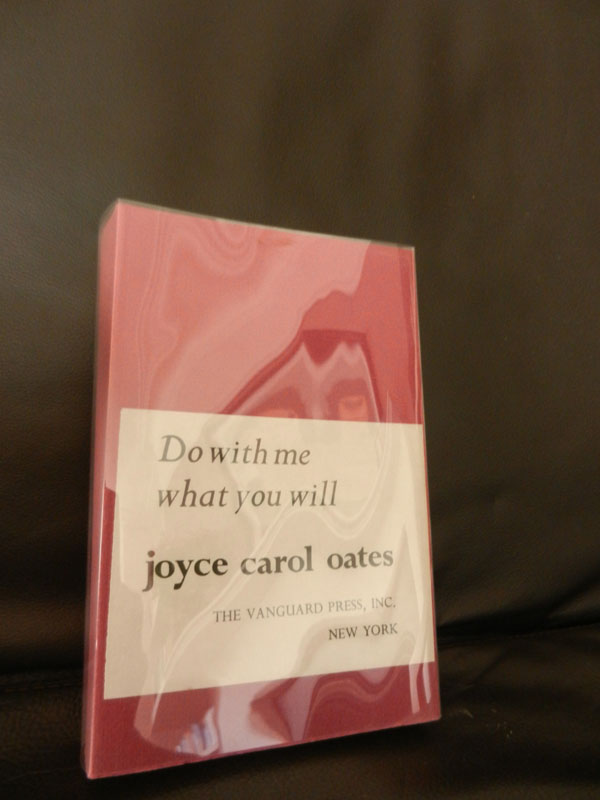

This is one of my top books in both monetary and sentimental value. It’s a proof of Joyce Carol Oates' novel Do With Me What You Will and inserted into the back is a typed revised ending from Joyce. However, both the ending printed in the proof and the new typed ending inserted within differ from the ending as it appears in the final published edition of this novel. It's a brilliant novel and well worth reading.

I’ve been lucky enough to see Joyce Carol Oates read several times. This copy of her published Journals means so much to me and is one of the few books I’ve read several times in its entirety.

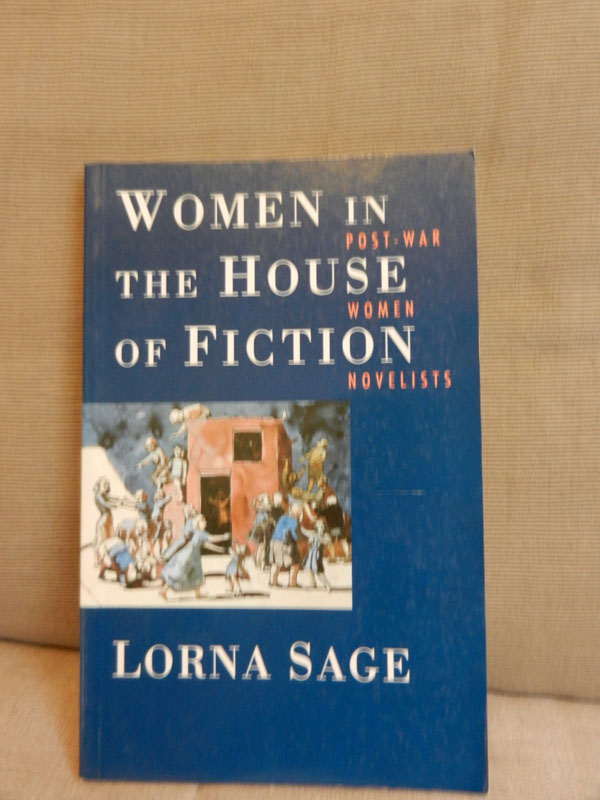

As part of my own personal tribute to my former teacher, the deceased author and critic Lorna Sage, I’ve been getting several authors to sign the tops of sections in which she wrote about them in this critical book about women and literature.

So what are some of the most treasured books you own?