Whenever I read a description of another new novel dealing with The Holocaust I feel a little twinge of uncertainty. Despite being one of the most horrific acts of genocide in the past century it’s a subject that’s been covered in countless novels. Is there anything new to say about this atrocity? Of course there is. Many novels from Audrey Magee’s “The Undertaking” to Ben Fergusson’s “The Spring of Kasper Meier” have proven this to me. But never has a novel I’ve read about this period of history felt more relevant and close-to-home than Rachel Seiffert’s new novel “A Boy in Winter.” I’m conscious that this has a lot to do with the current politics of our world, but I truly recognized in this story situations and patterns of behaviour that feel very near. Seiffert has fictionally dealt with this era before in her debut book “The Dark Room” which is composed of three novellas connected to the war and set in Germany. This new book is set in a small village in the Ukraine over a period of a few days in late 1941 when the Nazis come marching through “cleansing” the community of its Jewish population. It’s stunningly told and it’s a devastating story, but it also speaks so powerfully about the world we live in now.

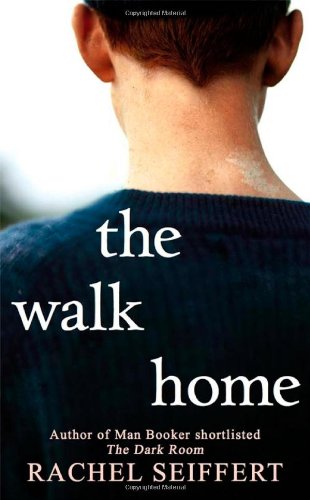

Seiffert has the most unique and powerful way of conveying the inner sense of a character’s emotions using only external descriptions. It’s something she did so expertly in her previous novel “The Walk Home” (which was one of my favourite books of 2014) and she does it again in this new novel with an adolescent Jewish boy named Yankel. Different sections of the book focus on different characters, but the author doesn’t often shine a spotlight on Yankel. Instead, we get a sense of him through other characters such as his father who has been put in a hellish temporary holding cell by the Nazis or a young woman Yasia who takes in Yankel and his younger brother. We get descriptions of the way Yankel carries himself, his stance or the movement of his eyes, but even though the reader is not often keyed into what he’s thinking we get a real emotional understanding of him from the author’s evocative external descriptions. Seiffert does this in a way which is powerful and quite unique. The arc of his story and the semi-tragic transformation he goes through in order to survive is brilliantly told.

This is an incredibly beautiful and impactful novel, but a slight problem I had with it is an instance where a certain character who is conscripted into the Nazi forces leads the reader through the way that Jewish people were processed. There’s nothing wrong with Seiffert’s descriptions of these scenes and their impact is devastating, but it clearly felt like his character was being used simply as a device to show what the author wanted to show rather than what his character would naturally encounter. However, a striking thing about this section is the way she describes the Nazis basically forcing each other to drink while they conduct their brutal and horrific executions. It gave a powerful sense of the way many of these soldiers had to use alcohol to deaden their humanity in order to perform the atrocious duties they were ordered to perform.

The central question of this novel asks what you would do if you were faced with the choice of following the evil will of an oppressive government or being severely punished for refusing to participate. It prompts you to ask yourself what you would do if neutrality wasn’t an option. Seiffert shows the complexity of this question through a number of different characters including non-Jewish Ukranians and a German engineer who takes a remote position in the army because he wants to avoid this moral dilemma but finds himself forced to make a horrific choice. The lines between an individual’s right and wrong become blurred when they are forced to ask themselves: “where was the wrong in staying alive?” It’s a haunting question.

I read this novel as part of a mini-book group I’ve formed with the writers Antonia Honeywell and Claire Fuller. We discussed it over lunch and had a fascinating conversation, but it’s quite special in that it’s the first book (out of the three we’ve read together so far including “The Underground Railroad” and “Mothering Sunday”) that all three of us were overwhelmingly positive about. Antonia and Claire are astute critics so the fact they both liked this novel so much is high praise! Rachel Seiffert is an incredibly talented writer and I find her writing moving in a way that is hard to describe. But it’s safe to say I’d recommend that everyone should read this timely historical novel.