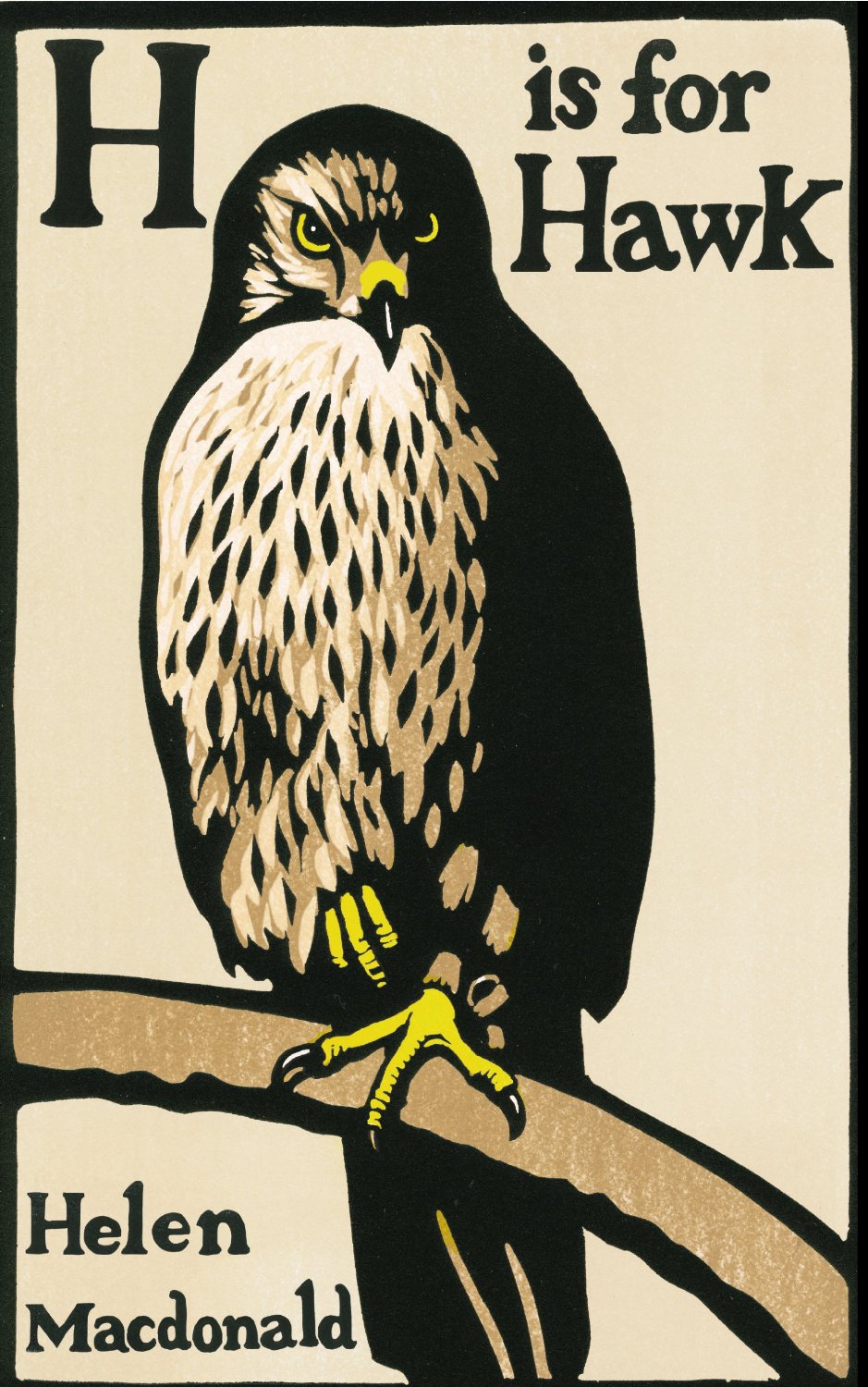

Do you ever read a book and are so intensely involved with it that it feels like a whole year has gone by rather than just a few hours? That was my experience reading “H is for Hawk.” I only started it on Monday and have been totally engrossed reading it during every spare minute that I can find. I had started reading Maria Semple’s re-released novel “This One is Mine” and didn’t find it that engaging so I switched to this book. Since it’s all about falcons I wasn’t sure it was going to interest me. But almost immediately the author reveals it’s also about the death of her father and the grief of dealing with this fact. To tell the truth, Helen Macdonald’s writing is so graceful and clever (yet highly approachable) that I would be interested in any subject she writes about. There’s a tremendous immediacy and directness to it – probably because she often addresses the reader as “you.” In this memoir she makes meaningful connections between her experience trying to train a newly-acquired young goshawk, the process of grieving for her father and the fascinatingly sombre life and writings of T.H. White (famed author of “The Once and Future King”). They seem totally disparate subjects on the surface, but White also had a great affinity for hawks and wrote a book about his (bungled) experiences trying to train one. Macdonald writes about approximately a year of her life in relation to these three subjects and the result is something which is devastatingly powerful. She writes: “What happens to the mind after bereavement makes no sense until later.” In making a retrospective survey of this emotional time period she organizes her thoughts about her unique process for dealing with death and finds profound universal meaning.

After she receives the shocking news of her father’s death, Macdonald gradually turns inward and becomes something of a recluse. In reality, I doubt she was as introverted as she makes out in the book. Whenever she encounters people she may think vicious or antisocial thoughts, but then acts quite civil and nice to them. She decides to acquire a goshawk which she names Mabel. On first seeing the hawk emerge from the box she hilariously remarks: “She came out like a Victorian melodrama: a sort of madwoman in the attack.” Goshawks are notoriously more difficult to train than falcons – which are the only birds she’s trained before. You learn a lot about hawks in this memoir as Macdonald has an encyclopaedic knowledge of them and the noble bird is a surprisingly fascinating subject. She spends virtually all her time gradually gaining the bird’s trust and taking it for short journeys in the surrounding countryside to hunt game. Meanwhile she maintains only a minimum amount of social contact with friends and family. Her teaching job comes to an end and she puts off looking for more work or finding a new place to live. Bills pile up and she tries not to think about the speech she needs to write for her father’s funeral. She becomes entirely consumed with the present task of caring for her hawk: “I could no more imagine the future than a hawk could. I didn’t need a career. I didn’t want one.” This period of solitude leads to an intense passionate kinship with her hawk. She becomes accustomed to the smallest changes in Mabel’s movements and expressions which betray the hawk’s thought process. Touchingly, the pair even eventually play games together with scrunched up balls of paper. But it’s always a wild creature and accidents involving small injuries to Macdonald are frequent. The hawk is independently minded and, without the promise of immediate access to food, Macdonald is highly aware that her hawk could easily fly away and abandon her.

Egyptian God Horus

After such an intense amount of time together there is a curious blending of identity which takes place. Macdonald becomes like the hawk as the qualities she admires in it are ones she desires to have herself. She notes that “By skilfully training a hunting animal, by closely associating with it, by identifying with it, you might be allowed to experience all your vital, sincere desires, even your most bloodthirsty ones, in total innocence. You could be true to yourself.” Although the experience of the hunt is a gruesome one, Macdonald finds a spiritual satisfaction in this act of nature. The complex emotions concerning the loss of her father which simmer just below the surface can be released through this savage process. She comes to understand that “Some deep part of me was trying to rebuild itself, and its model was right there on my fist.”

“H is for Hawk” is a highly unusual and meaningful book. It also happens to have an extremely beautiful cover. As a personal aside, I particularly appreciated a section towards the end where she travels to my home state of Maine for Christmas. Although this book is primarily about English country life, this section felt like a personal gift and a window to my childhood of snow covered fields, hunting and lobster boats.

We all experience profound loss at some time in our lives. This book certainly isn’t prescriptive about how you should overcome this, but it’s strangely comforting learning about Macdonald’s unique strategy for surviving losing her father. I’m not likely to ever become a falconer, but I can definitely relate to this beautiful statement which encapsulates so much about heartache and loss: “What you do to your heart. You stand apart from yourself, as if your soul could be a migrant beast too, standing some way away from the horror, and looking fixedly at the sky.”