Boys face particular challenges growing up. There’s often a weight of expectation to conform to certain gender stereotypes: to be strong, aggressive and withhold emotion. As adults we can more easily see how hollow this armour is, but when we’re young it’s difficult not to modify your personality trying to fit in with this brotherhood of masculinity. I grew up in a rural environment where I certainly felt this pressure. Men I knew hunted and made jokes while carving and gutting the corpses of deer they shot. They fished for the sport of it and released their living catch to swim frantically away, trailing a line of blood behind them in the water. Boys chased and sexually teased girls and laughed at them when they cried. I was ordered to chop wood outside for our fireplace while my sister had to stay inside to help with the housework. Whenever I questioned these gender roles I was laughed at or ignored. But most of the time I didn’t see the stark gender divisions in my community because it was all I ever knew.

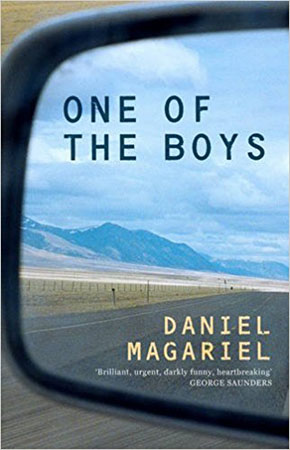

I was deeply moved reading Daniel Magariel debut novel “One of the Boys” by the way he presents an intense domestic situation of a boy living with his older brother and domineering father. He learns about what it means to join in with this cult of masculinity: its benefits and its pitfalls. There’s an exquisitely played out tension between his desire for validation from the men in his life and his desire to supersede or reject them. He and his brother choose to live with his mother over his father because “our loyalty had always been to our dad. He was stronger. We feared him. He needed us. His approval always meant so much more than hers – it filled me up.” The way in which they creatively expunge their mother from their lives is truly horrifying. His father continues to act badly becoming a habitual drug user, bullying people who oppose him and physically abusing his boys. What’s especially tragic about this is how the boy narrator learns that “My father would get away with this for a lifetime – the arrogance, the self-regard, the lack of consequences.” Boys see how abominably and brashly men can act without being taken to task for it and the result is that many of those boys grow into men who act the same.

What’s so impressive about Magariel’s style of writing is the crisp way he presents these ideas about gender in short declarative sentences that cut right to the heart of the boy’s experience and emotions. For example, after long periods of abuse from his father he paradoxically finds that “I didn’t want his kindness. His cruelty was less confusing.” With deft, impactful prose the author conveys complex ideas about the way this boy’s specific upbringing warps his conception about his identity, life and the way men should behave. This is also a short book, but the depth of this dramatic story of addiction, betrayal and poverty runs deep. It makes an interesting contrast to Edouard Louis’ recently translated novel “The End of Eddy” which presents a different portrait of how boys are inducted into typical masculine behaviour – especially when growing up in a working class community. It also reminds me of Justin Torres’ powerful novel about brotherhood “We the Animals” and interestingly Torres has a blurb on the book calling it “a captivating portrait of a wayward father.” With its moving story, this novel delicately prompts readers to consider how gender played a role in their own childhood and, for that reason, I think it will continue to resonate with me for a long time.