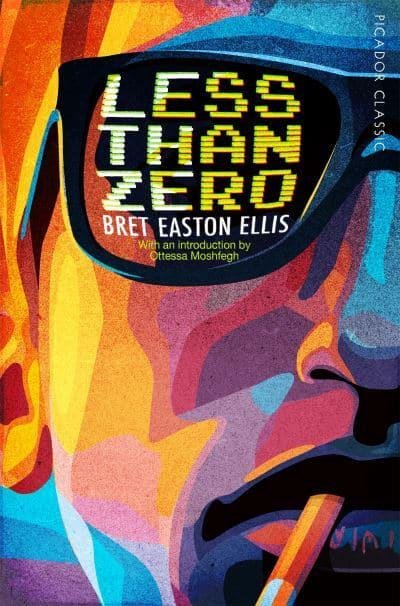

It was useful reading Bret Easton Ellis' debut novel “Less Than Zero” before diving into his latest “The Shards”. In this new novel a fictional version of 17 year old Bret is working on that first book and in this autofictional mode presents the story of his early life as a confession about the dramatic events which occurred during that formative period. (At the conclusion of the novel we're assured that this book is entirely a work of fiction.) It's 1981 and Bret is entering his senior year of high school in this uber-privleged side of LA with its mansions, servants, flashy cars, easy access to drugs and designer backpacks. Like in “Less Than Zero” we bear witness to this extremely beautiful and wealthy set of youth engaging in endless parties and sex. However, there is also a serial killer who has been dubbed “The Trawler” stalking the city's elite and murdering them (and their pets) in a gruesomely ritualistic fashion. The perpetrator(s) could be a deranged loner, a satanic cult prowling the city or the mysterious new boy at school, Robert Mallory, who charismatically worms his way into Bret's friendship group. Worrying signs reveal that the killer is getting closer and closer to Bret who becomes increasingly anxious and unhinged as his world of entitled excess implodes.

At its core, this novel is a very effective thriller with a rich atmosphere of suspense and tension. Real hazardous signs of violence appear even as we grow increasingly mistrustful of our narrator, a progressively paranoid (and medicated) Bret. As a writer for the large and small screen, Ellis is very adept at integrating elements such as creepy telephone calls, suspect vans which follow characters and a carefully judged release of information to consistently surprise and titillate readers. Bret's obsession over Robert is both intensely erotic and full of dread which builds a powerful sense of salacious danger. There's a clear propulsion to the story which builds towards its much foreshadowed “ironic and tragic conclusion”. The novel does feel overlong which is probably a hangover from it being initially written and released in serial form on Ellis' podcast. Though the author has stated a large chunk was edited out for the physical publication it still feels bloated as we get the back and forth gossipy details of these rich teenagers' vapid lives. The overly dramatic and cinematic denouement also feels a bit forced and unsatisfying with its gallons of bloodshed. Nevertheless, I felt mostly engaged throughout the bulk of the novel.

The book is also a kind of revisionist teen fantasy where Bret casts himself as being part of the most popular social group at his school. He's with a rich beautiful girlfriend whose father is a studio executive and he also gets to have lots of sex with two incredibly handsome guys on the side – details of which are related in highly descriptive detail. Though it doesn't actually happen, Bret even has a possibility of lunching with one of his literary idols Joan Didion. In this way, the novel feels like a curious blend of wish-fulfilment and nostalgia. Interestingly this pull toward the past was also present in “Less Than Zero” as Clay gazes longingly at buildings from his personal history. “The Shards” also reveals the degree to which Bret was inhibited by the sexual norms of the time. He felt pressured to have a girlfriend though he really longed for sex and a relationship with another man. There's an aching resentment over this but, of course, Ellis isn't the kind of writer who'd directly address this kind of oppression as a societal issue because it would involve engaging in identity politics – something I assume he rolls his eyes at.

It feels like a missed opportunity for emotional sincerity and showing the importance of gay rights as a means of attaining personal fulfilment. Of course, one could argue novels shouldn't have to engage in politics in this way but I believe if Ellis had done this the novel would have been more striking as it'd show growth and maturity. Instead what we get is very competent suspenseful fiction which refashions the same subject matter he first dealt with forty years ago. Only this time we get much more explicit detail about hot young guys and hot sex with those hot young guys from an author pushing 60. Sex positivity is one thing but it feels to me like this falls into yet more wish fulfilment by a man recasting his youth. On another level, Ellis does address a political issue but in a darker way. In one scene Bret accepts an invitation to lunch with Terry Schaffer, a powerful studio executive, about potentially writing a film script. However, it's abundantly clear that this is really an opportunity for this much older lecherous man to have it off with sexy 17 year old Bret. They do have hot sex and Bret walks away with a bleeding anus. Though he realises that he probably won't get the chance to put forward his script he comments when glancing in the mirror “I looked not only remarkably composed but as if I'd actually accomplished something – it wasn't what I wanted but it wasn't so bad. I was okay.” Given the very prominent discussions surrounding the MeToo movement in the past several years, it feels like this a direct rejoinder to this conscious fight to make accountable those who abuse their power.

Sure, it was a different time and it's just one character's personal experience but the way it's presented feels callous and disregards the vulnerability of younger individuals involved in a situation where the physical and emotional consequences can't always be anticipated. Instead of actually engaging with the complexity of this issue which has provoked many nuanced debates, Ellis presents a situation which blithely dismisses it. The larger consequences and meaning of such an exploitative exchange aren't addressed in “The Shards” any more than they are in “Less Than Zero” when protagonist Clay passively watches his best friend prostitute himself to pay off his drug debts. Certainly fiction should encompass all points of view, but personally I prefer them to be more sophisticated and artfully presented as in the novel “Vladimir” which shows the effects of power dynamics in cross-generational sexual relationships with more complexity. You could argue that Ellis shows the karmic consequences of this instance because Terry Schaffer gets his comeuppance but only in a melodramatic way that's not actually concerned with justice.

The annoying thing is that Ellis would probably eye any such critiques of his novel with a wry smile because I'm playing his game; I'm reading and discussing his novel; I'm making it all about Bret Easton Ellis because that's the subject matter Bret Easton Ellis is most interested in. In “The Shards” he comments that in writing “Less Than Zero” “it was about mebut there was no story”. So in this new novel he makes himself the protagonist as well as giving us a plot. It's effective on that level but the more I ponder this book and consider the way Ellis publicly presents his opinions the more it feels like a hollow egotistical exercise. I guess he wants to generate divisive opinions because it keeps him as the focus of attention – a technique successfully used by many populist leaders and megalomaniacs. So I'll sum this up by saying I'd recommend this novel if you're looking for a competent thriller, but bypass it if you're looking for anything more substantial.