In the past several months I've been thinking a lot about how my parents have influenced who I am. It's only become evident after some time and distance while making my own life in adulthood how patterns of behaviour can be seen in relation to how I was raised and how I reacted to them. I don't want to ascribe blame for any of my shortcomings on my parents' actions. It's simply interesting to observe and try to understand how the alchemy of nature and nurture influence attitudes and values throughout life. This novel acutely observes how “A life could be spent like an apology – to prove you had been worth it.” I believe that if we don't frequently reflect on the way our families have made us who we are the self becomes wayward, acting out in reaction to the past rather than working to better realize who we are in the present.

“The Portable Veblen” is about a couple who meet and marry, but it's much more a story about families and how two people can forge lives of their own coming out of very difficult family situations. Veblen is a thirty year old woman who lives on the remote edges of Palo Alto working secretarial temp jobs to fund her passion for translating Norwegian literature and studying her namesake Thorstein Bunde Veblen, a Norwegian-American economist. She freely quotes William James and sees herself as a curious kind of “travelling scribe” recording the lives of those around her. She meets and quickly falls in love with Paul Vreeland, a thirty-five year old research scientist who is on the brink of discovering a revolutionary new method for relieving cranial swelling and brain damage from head trauma. They want to marry soon, but planning a wedding isn't simple with families like these.

Veblen's mother Melanie is a hypochondriac who seems to have a new chronic medical condition every day and has a fierce emotional attachment to her daughter. Melanie's husband Linus, Veblen's step-father, tiptoes around his wife trying not to upset her and caters to her frequent unreasonable whims. Veblen's father Rudgear has been living for years in a mental institution as he suffers from PTSD and barely recognizes his daughter on her infrequent visits. Because Veblen has needed to take on a caring role for both her parents she still clings to childish fantastical notions of fictional lands filled with animals. It means she talks to squirrels.

Paul was raised under very different circumstances where his anti-establishment parents lived in a type of commune that grows marijuana. When they aren't engaged in sessions of chemically-induced escapism, most of their care and attention goes to Paul's mentally disabled brother. This upbringing has in turn made Paul very independently-minded and ambitious to gain approval from the establishment. However, his aspirations to achieve recognition in medical technology and bring his device to fruition entangle him in a corrupt system that his parents were rightly suspicious of. Alongside the story of his evolving relationship with Veblen is a plot about a corrupt medical industry that values profit over people's health care.

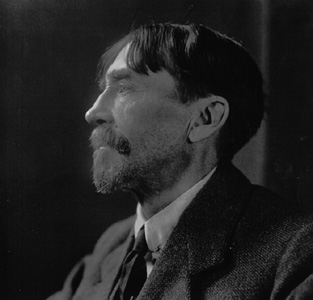

Thorstein Bunde Veblen

There are many cringe-worthy tragicomic scenes in this book as the couple meet each other's families and try to navigate how they can successfully integrate them into the life they want to build together. Importantly, the author doesn't mock the parents in this book or make them targets of derision for the ways they may or may not have fucked up their children. McKenzie takes care to show how they are capable of catering to their children's wellbeing when it's really needed. There is a tenderness of feeling present amidst the chaos as Veblen declares at one point “But you love your family, what can you do.”

It's interesting how McKenzie can introduce surprising moments of self-reflection amidst her narrative. As the characters' lives teeter on the brink of losing all control she can suddenly stop and ask searching questions which probe how the past and family life might influence the way her characters relate to their partners: “Was it possible to love the contradictions in somebody? Was it all but impossible to find somebody without them? Had her mother made of her a ragged-edged shard without a fit?” There is an endearing feeling throughout this novel of desperately trying to make sense of one's life while facing the challenges of life and trying to forge honest meaningful relationships.

McKenzie also has a fascinating absurd slant on the world. The squirrel Veblen maintains an occasional dialogue with becomes an important character himself and bends the plot of the story. Interspersed with the text of the story are occasional photos depicting a variety of things that Veblen either sees or imagines which make the reader more immersed in her view of the world. There’s an intriguing urgency to this author’s narrative which is more concerned with what her characters are thinking and feeling moment to moment rather than creating an organized structure to their journey or finding a clear consistent focus. She allows for moments of pause such as this: “She relaxed and watched a family at a table nearby, the parents feeding the children, wiping their mouths, cleaning their hands, a father and mother and two children, the unit of them unsettling to her, though she couldn’t say why. She looked away, at an older man eating by himself, and that unsettled her too. She wasn’t sure how to live.” Rather than developing her characters, McKenzie allows them to wade in uncertainty in a way which is strikingly poignant and meaningfully blunt.

“The Portable Veblen” is a curious book in that it isn’t afraid to keep asking questions for which there can be no solutions. I felt really connected to the story because of that and enjoyed the humorous and relevant journey of psychological insight it took me on.