Why do some people feel so compelled to write about their thoughts and experiences? Most of us are happy to let our perceptions and feelings recede into the back of our minds. Yet others, like Oliver Sacks have been compulsively writing journals, articles and books for the majority of his life. He describes in this autobiography how even at a concert he might sit writing constantly. It feels like this desire to write must come from an intense curiosity about the world and a desperate need to engage with it through the written word. By reading widely and conversing with patients, colleagues and friends, Sacks has been able to connect ideas and progress the field of neuroscience taking a more holistic approach where patients’ lives and experiences are taken into consideration. What’s more he’s able to eloquently shape how particular neurological disorders can enlighten our understanding of how most people perceive and interpret the world around us. “On the Move” is a direct, personal book where Sacks seeks to get an overarching understanding of his experiences and what has driven him to keep moving forward physically and mentally in life for over eighty years.

One of the fascinating things about this autobiography is that it shows how the physical process of writing itself is the way in which Sacks processes thought: “The act of writing is an integral part of my mental life; ideas emerge, are shaped, in the act of writing.” So writing isn’t necessarily where he tries to set out to a particular idea, but it’s where the process of thinking through his ideas actually takes place. It’s not surprising to read then that after finishing many manuscripts for his best-selling books he’ll go back and rewrite extensively or want to add innumerable footnotes because he is still thinking through his ideas and continuously adding to them. I believe this is why so many people who aren’t specifically interested in science can connect with Sacks’ writing – because of the overriding passion to truly understand which he demonstrates in his engaging writing. Given his seemingly-insatiable curiosity, Sacks has written an extensive amount and it’s somewhat tragic to learn in this book that many manuscripts have been lost over the years.

No doubt this autobiography will surprise many of Sacks’ fans who probably perceive him only as an introspective whiskered scientist. Yet we learn from early on in his professional life in California that “By day I would be the genial, white-coated Dr. Oliver Sacks, but at nightfall I would exchange my white coat for my motorbike leathers and, anonymous, wolf-like, slip out of the hospital to rove the streets or mount the sinuous curves of Mount Tamalpais and then race along the moonlit road to Stinson Beach or Bodega Bay.” Sacks has been an enthusiastic motorcyclist from early on in his life in England. Riding seemed to represent for him a freedom from the confines of his highly intellectual household. While his environment nurtured his intellect, he found it somewhat constrictive due to the homophobia of both his mother and the country at that time where “Public attitudes were, on the whole, as condemnatory as the law.” As many people have done, moving to California seemed to give Sacks the freedom to become the man he wanted to be in a more uninhibited way by pursuing the science which interested him the most, riding his motorcycle extensively, indulging in the mind-altering states of drug use and becoming a record-breaking body-builder. His recollections about the freedom he found in this are brilliantly vivid and engaging to read about. He’s anything but a sheltered geeky scientist!

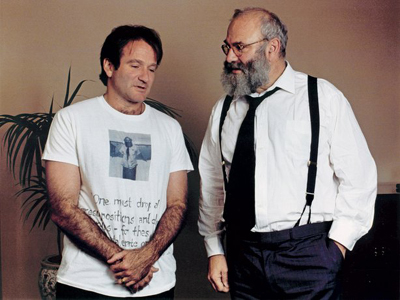

Oliver Sacks at the New York screening party for the movie of his book Awakenings, starring Robin Williams as a character based on Sacks, 1990.

It’s touching to read about Sacks’ friendship with the poet Thom Gunn. The title of this autobiography is taken from an exquisitely beautiful poem by Gunn. Sacks shows his own poetic sensibility in some of his descriptions of travelling on his motorcycle – particularly when it involves a level of romantic or sexual frisson. When riding on his bike with his friend Bud behind him Sacks describes how they were “so closely jammed together we sometimes felt like a single leather animal.” It’s admirable how Sacks seems to have been confidently assured about who his desires are directed towards from an early age. He meaningfully describes some of the strongest love affairs of his life – most of which weren’t long-lasting or reciprocated. However, there is a curious mystery presented when Sacks pointedly declares in one section that he became celibate and remained so for some thirty five years thereafter. There is a strange lack of reflection about why this occurred whether it was from guilt or shyness or a concentration on his profession or a simple lack of opportunity/interest. Having achieved his freedom in physically and mentally moving away from the constrictions of his English boyhood, he doesn’t indulge in long-lasting romance or sexual freedom. Of course, love is hard to find, but total celibacy seems more of a conscious choice than an accident. It’s difficult to know whether he refrains from discussing in this book why he thinks this occurred. Perhaps it’s something he’s reluctant to mull over or it simply doesn’t interest him. Nevertheless, it’s heartening when in the last chapter he describes finding a partner to lovingly share his time with in a way which is mutually supportive and beautifully nurturing.

“On the Move” is an extremely enjoyable and fascinating autobiography. It records a life lived with a rare degree of courage and love for the world around him. No matter the obstacles - whether they were a publisher rejecting him or a bull attacking him on a mountain in Norway - Oliver Sacks persevered and continued to engage with world around him. The physical acts of riding his motorcycle or, later in life, swimming every day seem physiologically linked with his desire to mentally push forward our civilization’s knowledge of science. I empathized a lot with Sacks reading this book and developed a tremendous respect for him learning about his experiences.