I listened to Simon and Thomas’ most recent podcast at the always entertaining and erudite Book Based Banter about the subject of Bookshops. It’s great hearing an in-depth discussion about favourite bookstores, thoughts about what makes an ideal bookshop and the possible fate of bookshops in the future. Hearing Thomas’ description of working in a bookshop where the staff had specialized knowledge and an enthusiastic interest in reading made me think back to my own brief period of working in a bookshop in Boston. I wish there were fond memories about it as being surrounded by books all day should have been a dream come true, but my experiences were anything but idyllic.

In the summer of 1997 I was nineteen years old and had just completed my first year as a scholarship student at a small college near Fenway. I dreaded the prospect of returning to my parents’ home in Maine for the summer. It was something I could have done but ever since I had come out to my parents we had a tense relationship. My father was accepting and loving (if baffled by the whole thing). He frequently travelled with his job so that left me home alone with my mother who had a really difficult time accepting it. The prospect of going back to a house where we’d be stuck together for long periods that involved shouting, cruel insults from both sides, dish breaking and – even worse – long periods of angry silence wasn’t something I could face so I decided to stay in Boston until my sophomore year started. A brilliant theatre teacher at my college generously offered to let me stay at her place near Forest Hills. While she travelled out of state doing theatre workshops the place was mine as long as I did odd chores for her.

My accommodation was taken care of, but I was broke. Not that I minded. Roaming the city was free. All I was interested in was burrowing away in books and theatre. I acted in an experimental theatre company that put on weird shows in an art gallery near Harvard Square which was brilliant but didn’t pay at all. I could have spent all my time rehearsing and reading. However, after a month and a half of living on scraps and staring into an empty refrigerator I realized that I did need to eat some time. I applied for a couple of menial office jobs but didn’t make it far. I guess it isn’t surprising thinking how I must not have been that presentable with my baggy clothes and shy nature. Even a fast food restaurant I applied to didn’t call me back. Since I didn’t have the money to buy books I sometimes went into bookstores to stand amongst the shelves reading new books that weren’t in the library yet. This was before the comfy chair bookshop culture with in-store Starkbucks. I’d read several chapters a day before I sensed the staff getting annoyed by my presence and move on.

So I was stuck until late July when I went by the Barnes & Noble in Kenmore Square and saw they were hiring temporary staff for August. They supply books for Boston University so needed extra help to stock and sell preparing for the students’ return. I applied and was thrilled when I got a call back hiring me. Working in a bookshop was something I should have thought of before since I spent so much time in them anyway and I liked the prospect of being able to work with staff who I assumed would also be enthusiastic readers.

On my training day there were about a dozen of us who were swiftly taken through an induction that taught us about stocking and learning the computer system. It was hurried and very confusing. I really didn’t understand the process of tracking down books on the computer and the managers training us were really overstretched as the shop was very busy. I asked for clarification but only received angry impatient responses. So I felt a little lost. The guy training us was a big buff guy who I tried to make light conversation with him asking what he liked to read. He looked at me in confusion saying “Read what?” I said I assumed he was into reading since he worked in a bookstore. He just laughed and shook his head, “No way man. I like to work out.” So much for talking about books.

On my third day working at Barnes & Noble I was asked with a few other men to help move bookshelves to a temporary space at Boston University they were setting up to sell course books. Not being very strong this was a struggle. I lugged and pushed shelves while the buff manager stood near me angrily saying “Come on, hurry it up man!” I went home that day worn out and with several bruises. Over the next few weeks the store was increasingly busy as students arrived back in the city and wanted their text books for upcoming classes. I still didn’t understand the computer system so helping them out was really difficult. Huge queues of people gathered at my till and angry teenage faces filled my vision as they thrust course lists with innumerable text books at me. I tried to stretch out my lunch breaks as long as possible hunkered down in the fiction section reading some book or other till they’d call me over the intercom back to the academic textbooks floor.

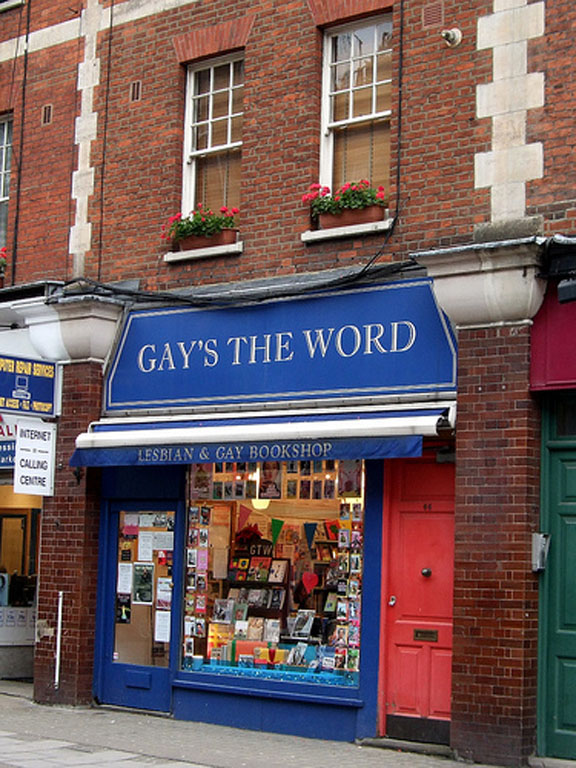

When it neared time to move back into my dorm and start my Fall semester Barnes & Noble said that I could stay on staff but only be on call if they ever needed me. Unsurprisingly they never called. So my short stint as a bookseller was a bit of a let down. It’s understandable it was a special sort of job as it was aimed specifically at supplying text books for the university. I’m sure if I worked in a general bookshop full time the vibe would have been different. I love going in shops in London like Gay’s the Word, Kennington Bookshop, Clerkenwell Tales or Daunt Books and hearing the friendly knowledgeable staff talk about recent books they’ve read or how they are able to easily navigate the shelves to find what I’m looking for. Not that I think anyone should romanticize it too much; I know it's a hard business. I’m fortunate enough now to be in a financially secure position where I can buy whatever book I’d like. This is something I’m really grateful for thinking back to times when I could barely afford to buy a 99 cent Dover Thrift book. Since living in London I’ve seen a lot of the used bookstores I used to love on Charing Cross Road and other places close down. The enormous Waterstones in Piccadilly Circus used to have a much better vibe with enthusiastic staff and frequent reading events by quality authors. These days their policy seems to be more towards only pushing the top sellers and the atmosphere has changed to being more brisk and businesslike. So I’m very grateful that there are still some fantastic independent bookstores with caring staff here. Long may they continue!