Amidst the tumult of the past four years it's been a balm when a new Ali Smith novel has annually appeared to herald in a new season, a new story and a new encounter with this author's inspiring imagination. “Autumn”, “Winter”, “Spring” and “Summer” have provided an invaluable frame for our recent times. So I felt worried when I read the beginning of her new novel “Companion Piece” which is described as being adjacent to the quartet or in the same family as this recent group of books. A character named Sandy states how “I didn't care what season it was... Everything was mulch of a mulchness to me right then. I even despised myself for that bit of wordplay, though this was uncharacteristic, since all my life I'd loved language, it was my main character, me its eternal loyal sidekick. But right then even words and everything they could and couldn't do could fuck off and that was that.” Oh no! Is Ali feeling so discouraged by the ongoing chaos in the world that she's feeling depleted? Well, frankly, who isn't? But, of course, the wondrous and surprising tale which continues on from this point shows that this author's creativity is still very much engaged and vibrantly active.

Sandy Gray is an artist whose elderly father is unwell and in hospital but it's “not the virus.” Visiting him is difficult as this takes place in 2021 while the pandemic is still causing restrictions when entering hospitals and what contact is allowed. She's also desperate not to get sick herself and inadvertently pass it onto her father so Sandy is limiting her interactions with other people. However, an unexpected call from an old classmate that she never even liked provokes a series of events leading to Sandy's house being colonized by a family that disrupts what's become her cautiously reserved existence. Those familiar with Smith's work will know that unexpected guests frequently appear and this novel is partly about what it means to let other people enter your life even when you don't want to interact with them. Given how isolated and distanced we've been from each other over recent years, this notion of letting others in is a challenge we all need to think about.

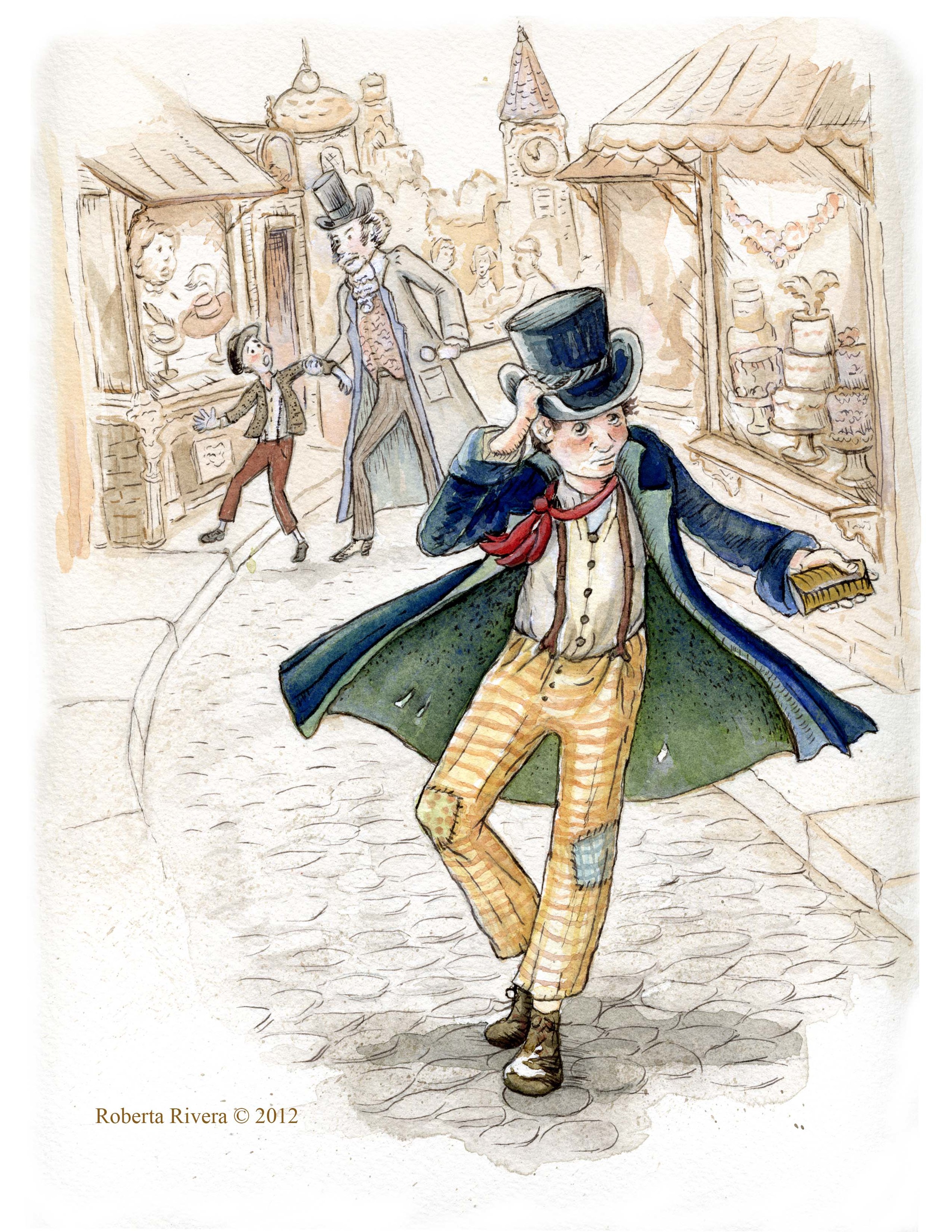

The invaders are not only individuals, but ghosts from the past. At one point a medieval girl and her bird come to steal Sandy's boots. Does this actually occur or is it a dream? That's not the question which this narrative is concerned with because “If any of this ever happened, if either of them ever existed. One way or another, here they both are.” Many more fascinatingly strange things occur over the course of the story as we're led to question not only the boundaries between people, communities and nations but between one period of time and another. A clock smashes and forms back into a whole. People are being categorized, shepherded into confined spaces and branded in different ways today just as they were hundreds of years ago. The shape and form may change but it's the same old story. This book is partly about that constancy, but also the light and dark which can be found in all these experiences. We may call the leaves of a tree green but they encompass a range of shades and an infinite variety of colours. This is what Smith's fiction celebrates.

We follow Sandy's development as disruptions in her life cause her to open up, consider new possibilities and have new encounters. Meeting someone can entirely change someone's point of view. Companionship can be found in a simple “hello.” Sprightly dialogue is interspersed with poetry analysis in a way which sparks unanticipated connections and new meaning. If we're attentive enough to the world around us we can see the mechanisms at play in language, in the ways we are governed and in nature. As in the Seasonal quartet, there are also references to specific political and social events to not only testify to what occurred in 2021, but remind us of what really happened because so many news stories are headlines one day and forgotten the next. Sandy's journey doesn't only bring her to one destination but allows her to see all the doors which are open to her. The novel beautifully shows that it's okay to take time to be alone just as it's okay to reach out to form a new connection, but we mustn't allow ourselves to become numb to what's occurring around us or the possibilities available to us every day.