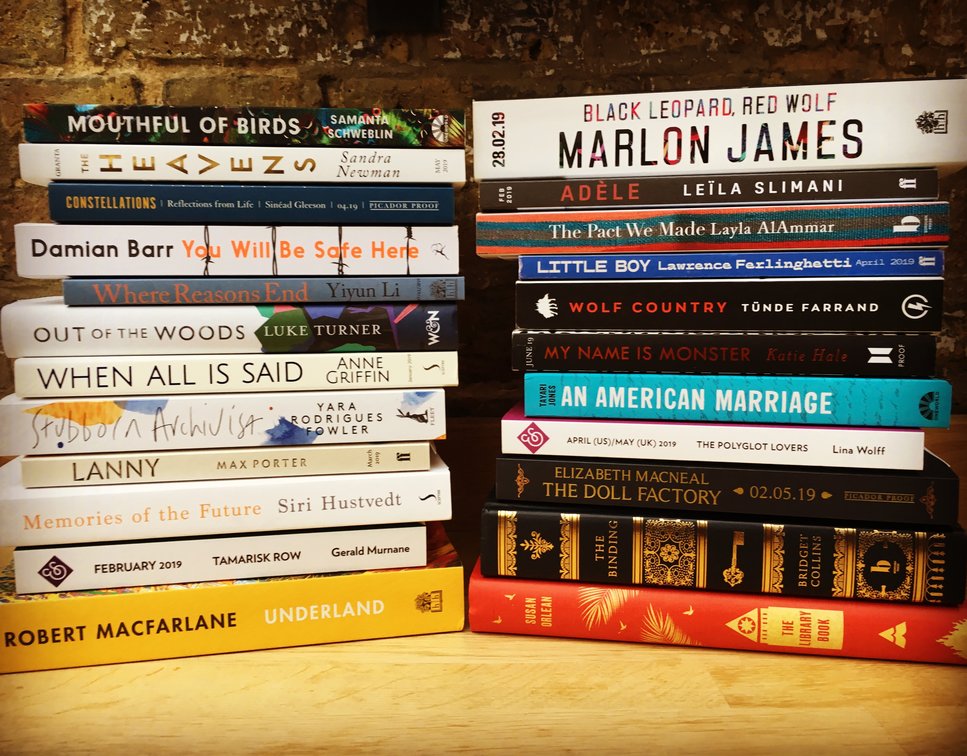

It's time to start making reading plans for 2019 and it's always exciting perusing UK publishers' upcoming lists to see what enticing reads are coming up! So here are some of my most anticipated books that will be published soon.

As soon as I got an advance copy of Marlon James' new novel “Black Leopard, Red Wolf” I couldn't wait to read it and plunged right in! It's an epic adventure like none other and I loved this stunning literary fantasy.

There are exciting new books by established authors I've never read before such as “The Library Book” by Susan Orlean and “An American Marriage” by Tayari Jones (whose novel has received praise by everyone from Oprah to Obama.) I had no idea that legendary beat writer & publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti was still alive but he turns 100 in 2019 and has a new novel out called “Little Boy”. I've been wanting to start reading popular travel writer Robert Macfarlane for ages and his new book “Underland” sounds like a great place to begin.

There are several debuts which sound so good including Irish novel “When All is Said” by Anne Griffin, dystopian novel “Wolf Country” by Tunde Farrand, experimental novel “Stubborn Archivist” by Yara Rodrigues Fowler, a novel about books and memory “The Binding” by Bridget Collins, Elizabeth MacNeal's hotly anticipated debut historical novel “The Doll Factory”, a novel about a young woman's life in modern day Kuwait “The Pact We Made” by Layla AlAmmar and poet Katie Hale makes her fictional debut with an incredibly inventive sounding novel “My Name is Monster”. I loved the anthologies of Irish women's writing edited by Sinead Gleeson so I'm thrilled she has a debut collection of essays out “Constellations”. Then there is debut memoir “Out of the Woods” by Luke Turner about confronting uncomfortable emotions after a bad break up. But one of the most anticipated debut novels of the year is “You Will Be Safe Here” by memoirist, journalist and literary-salon extraordinaire Damian Barr.

Some beloved authors I follow closely and it's always exciting to hear they have new books coming out. Having read French author Leila Slimani's breakout last year I'm really excited to read her new novel “Adele”. Yiyun Li's memoir was one of my favourite books of 2017 so I'm really eager to read her new novel “Where Reason Ends”. I was equally mesmerised by Samanta Schweblin's debut novel and hear her new book of short stories “Mouthful of Birds” is equally eerie and compelling. Max Porter is one of the most exciting writers today having been crowned The Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year in 2016 for his debut and his new novel “Lanny” sounds riveting. Another seriously innovative writer is Swedish Lina Wolff whose new novel is called “The Polyglot Lovers”. I'm hooked on Siri Hustvedt's intelligently powerful writing so her inventive new novel “Memories of the Future” is a must. One of the most challenging and rewarding novels I read in 2015 was by Sandra Newman and her new novel “The Heavens” sounds incredible!

There will also be new novels by Joyce Carol Oates with “My Life as a Rat”, Helen Oyeyemi with “Gingerbread” and Rowan Hisayo Buchanan with “Starling Days”. As I already discussed in my video about the announcement of a sequel to “The Handmaid's Tale” Margaret Atwood will be publishing “The Testaments” and with Elizabeth Strout revisiting her ornery heroine Olive Kitteridge in “Olive, Again” it looks like 2019 will be the year of literary sequels!

You can also watch me discussing all these books here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bZJnfnt8rAU

What books are you most looking forward to in the new year?