Earlier this year I read the moving memoir “Mind on Fire” in which the author recounts his experiences with manic-depression, suicidal thoughts and the destructive impact his mental health issues have upon his personal relationships. An experience similar to this is dramatically rendered in Rowan Hisayo Buchanan’s new novel “Starling Days”. It’s the story of Mina and Oscar, a young married couple living in New York City who temporarily move to London so Oscar can help his father prepare some run-down properties for sale. But Mina struggles with feelings of sadness which threaten to overwhelm her and self-harm. Her issues with mental health are portrayed with equal weight against Oscar’s no less heartrending emotional negligence being born as an illegitimate child who seeks to forge a connection with his aging father. Amidst their struggles, Mina makes a strong romantic connection with Phoebe, a red-haired English blogger whose presence brightens the world for Mina when she begins to feel overwhelmed by a suffocating loneliness. It’s noteworthy how this novel realistically and sympathetically portrays the experiences of a bisexual character. But Buchanan portrays all her characters’ journeys and dilemmas with a great deal of sympathy that made me feel wholly connected to them.

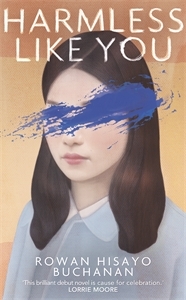

This is only Rowan Hisayo Buchanan’s second novel but I can already see she has a touching methodology in her fiction for portraying the lives of distinct individuals who are powerfully connected. Her first novel “Harmless Like You” depicts the lives of a mother and child in different periods of time. In a similar way, “Starling Days” gives equal weight to two characters’ perspectives and how their personal struggles create severe challenges in their relationship. But the author has a magnanimous way of rendering the daily reality of their situations without making any judgements. She conveys in their dynamic how there’s no perfect way to go about helping someone dealing with depression and suicidal thoughts. It’s not something that can be neatly fixed. It’s more like a balancing act between therapy, medication, attentive loved ones and an inner drive to continue. We see how Mina must consider these every day while also grappling with feeling like a burden because of her condition.

It feels as if Buchanan is slightly playing upon recent trends in literary fiction to invoke or retell Greco-Roman mythology through a modern perspective. In preparation for writing a tentative academic monograph Mina loosely researches stories of the few mythological women who survive in their tales since so many female mythological characters die through punishment, their own folly or cruel coincidence. Rather than creating her own fictional account of these women Buchanan references their stories amidst Mina’s own plight. It creates interesting points of comparison but also provides a poignant frame in which to see Mina’s journey as a literal struggle to survive amidst the beaconing hand of death. There’s also a playful sense that Mina is more able to understand the tragedy in these epic tales than the inscrutable complications found in modern life: “This world made so much more sense if it was filled with angry, hungry gods.”

As moving as I find Buchanan’s writing, she has an occasional tendency to needlessly complicate some sentences in order to emphasize the physicality of her characters’ movements. So she’ll write “Her hands picked up her phone” when she could have instead just written “She picked up the phone.” Or “His legs carried him down the stairs and to the hall” instead of “He went downstairs.” This clunky phraseology can be distracting. But overall her writing has a pleasing fluidity to it in evoking all the undercurrents of emotion within her characters’ lives as they navigate the world and interact with one another. This is most powerfully rendered in the dialogue and communication between characters who gradually disconnect from one another until the reader can feel the sad gulf which exists between them.

The novel poignantly considers the complications involved in relationships steered by dependencies that are emotional, financial and/or sexual. It’s not necessarily bad that such dependency exists because it necessitates a level of openness and vulnerability that’s needed in a strong relationship, but it can create a hierarchy and possessiveness which can impact upon people’s sense of self-worth. Fully accepting yourself while also truly loving someone else is difficult. “Starling Days” powerfully shows the nuance of such connections and it gives the story a rare clear-sighted honesty.