I was interested to read this fictionalized version of Zelda Fitzgerald’s life as I

know so little about her. My only impressions about her from talking to friends

and reading about F Scott Fitzgerald’s life was that she spent some time in a

mental hospital, had her own literary ambitions and possibly derailed her

husband from producing as much work as he might have. These are the kind of brief

biographical details that we sometimes lazily cling onto to rather than taking

time to investigate the full complexity of the person and that we are prone to

believe because we are always handed a subjective view of history. As the

author notes in her afterward: “Where the Fitzgeralds are concerned, there is

so much material with so many differing views and biases that I often felt as

if I’d dropped into a raging argument between what I came to call Team Zelda

and Team Scott.” We can’t ever know what really happened in this long and

tumultuous relationship. However, what is clear is that Zelda was a passionate,

troubled and highly artistic individual. Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald sheds

light upon the inner life of this fascinating woman and the sexist attitudes of

the time which often stifled her own artistic endeavours.

The novel

takes us from the time Zelda is a teenager first meeting Scott through to the

disintegration of their marriage and the end of Scott’s life. At the start

Zelda comes across as quite an ordinary girl from a distinguished family who

goes to parties and flirts with young men. When someone asks Zelda “There’s

more to life than fellas, right?” Zelda replies: “‘Not really,’ I said. My

smile felt weak, but it was a start.” Her whirlwind romance with the charming

and ambitious Scott takes her to NYC and eventually Europe

where the pair lead lives filled with drink, parties and endless socializing. One

is suspicious of the simple elated excitement and wonder Zelda exhibits without

showing a trace of fear or uncertainty or sadness, but this throwing herself

headlong into the giddy rush of it all serves as a hidden warning for the

tricky times ahead.

When the

party wanes Zelda becomes a much more interesting character because of her own

greater appreciation for and engagement with the world. At one point she

observes, “For the first time, I had a glimmer of the immensity of the planet,

of lives being lived as routinely or as vividly as my own had been at any given

moment.” She also grows from someone who is complacent in the subjugation of

women: “I ended up with a black eye. I was of the mind that I deserved what I

got.” to someone who understands it’s necessary to stand up for herself as she

comments later in the novel “It was so much easier to be led, to be

pampered and powdered and petted for being an agreeable wife. Easier, I

thought, but boring. And not only boring, but plain wrong.” However, standing

up for herself and expressing her own voice is difficult given Scott’s own

misogynistic attitude toward Zelda and his attitudes about women in general.

The vision of liberated free-acting women portrayed in his novels turns out to

be a sham. Scott says at one

point “All of that flapper business was just to sell books.” This attitude most

likely partly stems from Scott’s own fears that Zelda’s artistic powers might

compete with his own. Unfortunately, this oppressive nature is reinforced

institutionally at the psychiatric clinics she enters into where she’s told to

write about the correct role of women in the household and by her own family

and many of their social circles. At Gertrude Stein’s literary salons the wives

(Zelda included) must sit apart drinking tea while Stein herself and the men

talk art. Also, the powerful and threatening figure of Hemmingway looms large

in the novel. Initially he is a kind of protégé of Scott, but then becomes a

well known author himself who drives a wedge between the couple by continuously

making Scott believe that Zelda is hobbling his artistic abilities and holding

him back. Meanwhile, Zelda suspects Hemmingway might be a “fairy” and have

designs on her husband that involve more than literary kinship. Generally in

this book Zelda’s viewpoint seems to be a trustworthy one. However, when it comes to her perspective on Hemmingway one wonders if her opinion isn’t skewed due to jealousy

and personal bias after a disturbing encounter where Hemmingway propositions

her. What is clear is that Hemmingway is a calculating social climber who works

too hard to prove his machismo. He is accustomed to using people especially for

his own sexual gratification and to advance his literary career.

When the

glitzy cloak of success starts fraying at the edges and the endless parties and

boozing take their inevitable toll Zelda and Scott’s relationship really starts

to feel the strain. Scott is shown to be someone convinced of his own literary

genius, but also harbours a tremendous amount of insecurity. Often he prefers

drinking, socializing and whoring over getting down to the tedious business

with pen and paper. As money troubles mount he even starts to let short stories

written by Zelda be published under his own name in order to receive greater

payments and to enhance his own literary standing. Zelda grudgingly accepts

this, but it adds to her increasing mental strain. Throughout much of the novel

it’s as if Zelda is viewing her life by looking through a cracked window making

wry comments about her relationship with Scott, artist-packed soirees and

stuttered attempts to make a career as a writer or painter or dancer. Towards

the end of the novel, her viewpoint becomes more fragmented as she mentally

breaks down from the ever towering strains of her physical problems,

misdiagnosed psychological problems, tumultuous relationship with Scott, lack

of recognition for her own achievements and the weariness which comes from

partying hard like a true woman of the Jazz age.

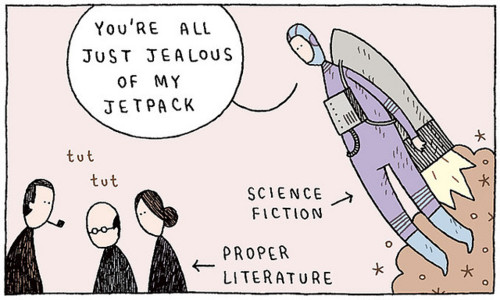

There have

been many other books which fictionalize the lives of writers to give insight

into their personality and the circumstances which went into creating their

body of work. Some of the most accomplished I’ve read are CK Stead’s novel

Mansfield, the Virginia Woolf portion of Cunningham’s The Hours and my

favourite of all Colm Toibin’s novels The Master (about the life of Henry

James). It’s difficult to resist peering through the window into what the lives

of these authors might have been like – a strange impulse given how writers

often lead reclusive and quiet (ie dull on the surface) lives. Of course, great writing speaks to our

souls and, while we might like to believe we’d have a spiritual kinship with

the author of such great thoughts, the actual person might turn out to be deeply

flawed and disappointing. After reading Fowler’s novel I can’t help but feel suspicious

about Scott Fitzgerald and Hemmingway knowing that their personalities probably

in some ways mirror their fictional versions. Not that I won’t still be able to

appreciate their work, but I’ll be more guarded when approaching it. What’s particularly

excellent about Z is that it establishes Zelda was an artist in her own right

(albeit, one who is little read now and usually only by fervent fans of her husband)

and a woman who is largely misunderstood (as is shown by my own vague prior

impressions of Zelda.) So this novel has given me much greater appreciation for

the complexity of her life and understanding of how lives of terrific excess

can fuel and finally extinguish the flames of creativity.