The year is flying by and so many great books have already been newly published (including so many I’ve still not got reading). It was difficult making this list because I’ve read 48 books so far this year, many of which were excellent. I’m only going to mention 10 here. But I’d love to know some of your favourite books so please leave a comment to let me know about your top recent reads. If you want to know more of my thoughts about any of these click on the titles for my full reviews.

Go Went Gone by Jenny Erpenbeck – This is a novel, longlisted for the Man Booker International Prize, about a retired professor in Berlin who becomes involved in the lives of several refugees. It’s a topical story about immigration, but I think it’s also so much more than that too. It’s a really emotional story with a teasing mystery at the core of its protagonist and it also contains such profound philosophical thoughts about identity.

Sight by Jessie Greengrass – This debut novel was shortlisted for the Women’s Prize and I made a silly early prediction that it will win this year’s Booker Prize. Readers’ reactions to this novel have been very polarized. It’s a very particular kind of introspective story that won’t be for everyone. But personally I loved it for the way it shows the transition in identity from child to parent and the artful way it blends nonfiction with the pressing ontological issues its protagonist faces.

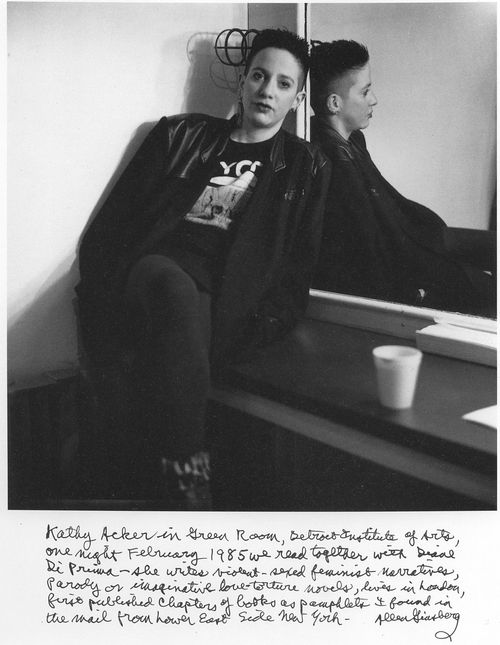

Crudo by Olivia Laing – Laing’s nonfiction has shown how she has a very personal and intelligent way of looking at historical figures. Her first novel Crudo really cleverly blends her passion for the writer Kathy Acker with her own preoccupations about modern life. The more I think about this novel the more it affects me. It speaks so meaningfully about this crisis we feel inhabiting our bodies and minds in a chaotic world where global politics that are increasingly bleak and how challenging it is wrestling with our own egos every day.

Tell Me How It Ends by Valeria Luiselli – I can’t think of another book that has proved to be so relevant to the immediate emergency Americans recently faced concerning illegal immigrants and refugees being forcibly separated from their children. Luiselli describes her experiences speaking to asylum seekers who are children and the reality of their crisis in a way that is incredibly enlightening. When I read this a few months ago I said this short book should be required reading for every school in America, but I think it should be required reading for every adult as well.

The Sealwoman’s Gift by Sally Magnusson – This historical novel is based on the true story of a large group of Icelandic villagers kidnapped and enslaved by Barbary pirates in 1627. Many are forcefully taken to Algiers and this novel mainly focuses on the story of the plight of a reverend’s wife. It may sound bleak and there are distressing scenes but it is also richly detailed, beautifully told and intensely poignant in the way it asks questions about: where do you belong?

Beautiful Days by Joyce Carol Oates – A book of short stories that are intensely dramatic and show a magnificent range from tales of stark psychological realism about the conflict between lovers or the conflict between a mother and her son to stories that are slightly more surreal in tone like an ex-president forced to dig up the graves of all the victims of his policies or a girl trapped in a painting like some nightmare fairy tale. They are so imaginative and gripping and this is the second book of short stories Oates has published this year. Her other book Night Gaunts is equally as compelling and you can watch me talk at length about these HP Lovecraft-influenced stories in a video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ekmgrCyZqDg&t=155s

Fire Sermon by Jamie Quatro – This novel describes a woman who is a wife and mother and how she enters into an affair. It’s well-trodden fictional territory but Quatro speaks about it in such a thoughtful and considered way. It shows how challenging it is to grapple with our desires – not just our desire for sex – but also for an engagement with someone that is intellectual and spiritual. And it gives such a sobering take on how messy all this unruly passion is.

Problems by Jade Sharma – This debut novel is about an anti-hero named Maya who can’t connect with life in the way she knows she should. Her marriage is inane. Her lover is distant. Her job at a bookstore is going nowhere. Her thesis is unfinished. Her mother is nagging. Her drug habit is getting worse. She's self-conscious about her body size, her skin colour and her very non-PC sexual impulses. But through all this the author has a frank candour and humour which makes this novel oddly comforting in a way that acknowledges what a disaster all of our lives really are.

Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith – I was lucky enough to see Smith read some of the poetry from this book in person. He is such a passionate and lively reader. And these poems are so engaged and revelatory in how they speak about black bodies in America, gay culture and being HIV positive. They’re politically aware and playful and sexy. Even if you’re not someone who normally reads poetry, I think anyone can connect with this incredibly original and relevant writing.

And finally, not a new book, but a classic. Frankenstein by Mary Shelley! I’ve been reading more classic novels than I usually do – not just for some Rediscover the Classics campaigns that I’ve been curating – but also other books and it’s been so enlightening. And it was such a joy to read Frankenstein for the first time and it’s appropriate too since it’s been 200 years since this novel was first published. It really wasn’t what I expected as it was so much darker and complex and philosophical than I thought it’d be.

So those are my choices! I feel glad to have read such amazing books and I’m sure I’ll discover many more great reads in the next six months. Now I’d love to hear about what books you’ve most enjoyed so far this year.