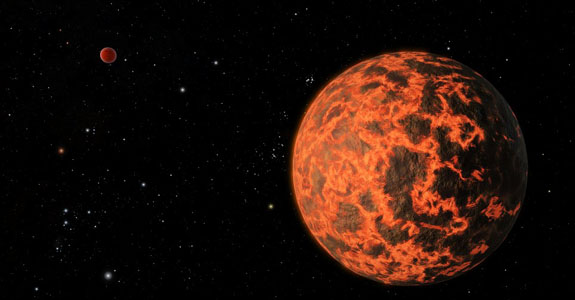

Apocalyptic visions of the future usually brim with dramatic conflict amidst large-scale destruction in society. Jenni Fagan takes a much more soft-treading and realistic approach to representing probable outcomes of climate change in her novel “The Sunlight Pilgrims” where a group of characters hole up in a Scottish caravan park for the onslaught of a cataclysmically cold winter in the year 2020. Rather than any explosive end to civilization, it seems much more likely that in the future life will still continue much as it does now until the effects of rising global sea levels make an unavoidable difference to our daily lives. Here it’s represented by a slow-moving iceberg making its way to the British Isles. Meanwhile many huddle within the commercial comfort of IKEA hoping that it’s not really happening. Amidst this coming crises, a fascinatingly unique group of characters at the margins of society deal with their own personal struggles while preparing for the coming of another Ice Age.

Central to the story is the beautifully realized character of Stella, an eleven year old who was biologically born a boy named Cael. Stella has been ostracized from the social groups she so recently enjoyed easy companionship with. She finds it particularly painful that a silence now exists between her and an attractive boy named Lewis who once kissed her. He bows to the peer pressure from his friends who mock and attack Stella for being transgendered while secretly still harbouring feelings for her. Stella also faces institutional challenges from a doctor who refuses to prescribe much-needed medication to block the hormones which are causing her to grow into a male with emerging facial hair and a deepening voice. Nor will he speed up a referral to a specialist who would hopefully be more sympathetic to her condition. This causes her internal anguish being trapped in the wrong body where “she feels like sprinting away from herself.”

Luckily Stella’s mother Constance rallies to her daughter’s support and fights for the justice that the vulnerable child isn’t able to insist upon herself. It’s touching how she exhibits total love for her daughter while struggling with private feelings of mourning for the son she has lost. It is also lucky that she’s strikingly capable in matters of survival ensuring that her family and those close to them are well prepared from the impending potentially lethal freeze. She’s someone that has been relegated to the margins of the community due to her unashamedly non-monogamous love affairs – for many years she maintained a simultaneous relationship with two men.

The mother and daughter meet a new neighbour in the park named Dylan who recently moved from London after the death of his beloved mother and grandmother. They left him a trailer in this remote village of Clachan Fells which he’s had to retreat to after the closure of the family-owned London arts cinema where he was raised. Dylan muses frequently upon his bohemian upbringing and the strong, compelling women who raised him. His grandmother Gunn MacRae won the cinema in a poker game when she was younger and maintained a bracingly liberal attitude towards sex stating in one dream-sequence: “always have a lover on the side or you might as well be dead.” Poring over things left by Gunn and his mother Vivienne, Dylan gradually discovers that his familial links to this little community are more complex than he first realized.

"Fronds of ice have all blown in one direction, creating feathers"

Fagan's writing has a remarkably poetic quality when she describes scenes of tremendous emotional conflict. In one of the most striking and emotional moments in the novel Dylan climbs up a mountain during particularly foggy weather. Troubled by his grief and memories his body seems to disintegrate into the haze. There follows a remarkable fluidity between the internal and external landscape which I found so beautifully moving and effective. Paired with these lyrically-charged passages, Fagan is equally skilful at writing punchy dialogue which brings life to the characters and grounds the narrative in realistic scenes.

“The Sunlight Pilgrims” is a beautifully written and chilling vision of the future with refreshingly original characters.