Amidst the general confusion, fear and suffering caused by the global pandemic, I've also found it worrying to see the disruption to many writers, publishers and booksellers. The financial and emotional strain was instantly palpable on their social media, newsletters and websites. The work of many writers and journalists instantly evaporated. Publishers pushed forward publication dates for many books. Bookshops still grapple with the question of when and how they can properly reopen. As an ardent reader outside of the publishing industry it's distressing to watch the people who create the new books I dearly love feeling such hardship. When economic prospects are bleak it's the arts which are typically viewed by governments as expendable. But it's these people who are best equipped to articulate, chronicle and offer an artistic form of solace amidst the extraordinary circumstances we're in the thick of struggling through. This is exemplified by the quick response of several authors from around the world who've contributed to this new anthology “Tools for Extinction”. Included are new pieces of fiction, poetry, essay and memoir which artistically respond to our current times.

I'm greatly impressed with the speed at which this book was put together but also that it takes a global view from authors from nearly every continent and many different cultures. In a time of such extreme physical separation and when it's impossible to know when I'll be able to travel internationally again it's comforting to hear the immediacy of these voices from around the world. It's also touching to see overlapping observations between countries whether it's the experience of viewing individuals smoking on distant balconies or similar feelings of loneliness felt in very different locations. Enrique Vila-Matas notes how swiftly the pandemic changed from something distant in our screens to arriving on our doorsteps. Berlin-based Anna Zett describes the closure of a local bar and the competing points of view of a circle of friends. Patricia Portela's story is overcast with a newly ominous feel as it concerns an individual desperate to travel abroad. Days can't be measured in the same way now that the sounds of the school opposite her home have gone silent in Olivia Sudjic's piece. Michael Salu's poem describes how banal and small our personal reality has become: “There is repetition and there is routine \ my own reality \ emerges from prison.” Jakuta Alikavazovic's anxiety/insomnia drives her to count coins in a jar. Vi Khi Nao observes how the unnatural denial of physical intimacy and demarcated personal distance means “The world is a place where cruelty has all the swords.”

While some authors vividly describe the immediate impact and vivid fear caused by this virus others feel far removed from its physical effects but experience psychological disturbance. Norwegian author Jon Fosse details a nightmarish scene where the narrator is persistently chased and seeks spiritual communion. Anna Zett's 'Affinity Group' also describes how the pandemic can be a catalyst for personal revelation: “Outside of computer games, the final enemy is just the victim I used to be, projected into the future and onto another body. With the final enemy, it's just like with the apocalypse. If I refuse to let go of the past, I can easily predict what will happen if liberation fails or if love isn't found.” Other authors also consider how the current events can offer an opportunity for new perspectives. Joanna Walsh's illuminating piece 'The Dispossessed' questions how stories are formed in retrospect: “Narratives belong to those left alive. But they're told about what has ended. That's the paradox. You can never peep in on your own obituary to read about your life and what it meant.” Jean-Baptiste Del Amo considers how these circumstances can expose what should have been obvious before: “A virus can be a revelation: it can reveal the limits of economic growth, of cynical profit seeking, of mechanisms of power in a capitalist system.” Similarly Greenland-born author Naja Marie Aidt notes how recent events have made “the inequality as visible as the tiny virus is invisible”.

Some pieces make no mention of the pandemic at all reminding us that there are a multitude of concerns that are totally separate from the top news story of the past several months and how there are other local and national issues which continue to fill our lives. Mara Coson creatively blends song lyrics with descriptions of large-scale natural disasters. Danish writer Olga Ravn movingly considers the closeness or distance felt between a mother breast-feeding her child. Inger Wold Lund's piece (which can also be listened to in audio form through the publisher's website) provides instructions to the reader/listener to be grounded in the reality of their immediate surroundings. Meanwhile, Frode Grytten's poem makes a distress call to the future.

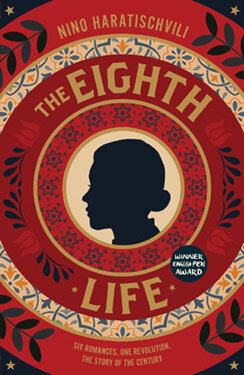

I found it comforting to meditate on these many different points of view. Together these pieces offer a refreshing range of new perspectives which reach across a globe that has become as distorted and flattened as the image on this book's cover.