In my late teens and early adulthood I had a particular fascination with both utopian and dystopian fiction – so naturally “The Handmaid’s Tale” made an appearance on my reading list. But that was many years ago. Rereading it now as a more socially and politically aware adult I think I’m sensitive to many aspects of it that I probably wasn’t conscious of when experiencing this story for the first time. Back then I probably primarily read it as a thriller about a woman torn from her husband and child and forced to live in sexual subjugation under nightmarish circumstances. But that wasn’t the only way I connected with the story. I related to it and understood the shroud of silence Offred must maintain in order to survive. When I came out as gay in my teenager years I was explicitly instructed by my parents, teachers and school guidance counsellor not to speak about this facet of my identity with people in general. So my strongest memory of reading this novel was in the canny way Offred chose her moments to reveal her true beliefs and feelings to others rather than toe the line.

When I first read this novel I was struck by the way Atwood describes how the Republic of Gilead punishes homosexual acts with hanging and, of course, I was aware that such executions have been carried out by many oppressive regimes over time. I was struck that Offred’s lesbian friend Moira was in a particularly vulnerable position. The bitter poignancy of Offred’s eventual reunion with her in a brothel felt particularly sad. It made me consider what compromises must to be made for the sake of survival. Like Offred, I had hoped she’d become a revolutionary fighting against the regime after escaping from the government-trained Aunts. I was aware of the cost of sacrificing one’s own safety and security for the sake of a larger cause, but I still thought Moira was cowardly for not taking a stand. But reading it now I feel Moira’s pain more acutely: the deleterious effects she must have felt smothering her own values for the sake of living and the crushing hopelessness knowing an act of rebellion would be futile because it would only end with her own death.

So my reactions to reading this novel that first time were mainly centred on the way I personally related to its story. While I don’t think that’s a “wrong” way to read the novel, I’m more conscious now (as Atwood has famously and repeatedly stated) that there’s nothing in this novel that hasn’t occurred in real life within some society. It’s a point which is even emphasized at the end of the novel when the speaker presenting a lecture regarding Offred’s transcribed tale describes how the Republic of Gilead’s policies are an amalgamation of different practices and regulations from a selection of governments. But I was reminded of the real-world relevancy of the novel again recently when reading the memoir “My Past is a Foreign Country” by Zeba Talkhani because the author remarks how she didn’t consider “The Handmaid’s Tale” fiction because it felt like her reality when growing up in Saudi Arabia.

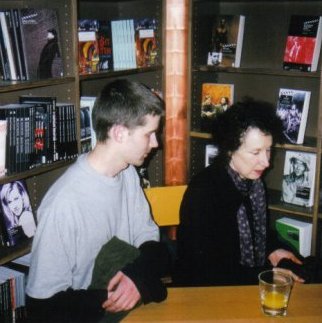

When I met Margaret Atwood on my first trip to London in 1999

When reading Offred’s tale this time I thought more closely about these parallels and the realities being portrayed in the story. Certainly there’s been a lot of progress in the world since this novel was first published in 1985. But, at the same time, I think many of us have a pressing awareness how the patriarchy will always try to control and regulate women’s bodies as well as suppress any voices which pose a threat to its power structures. So it feels not only relevant but entirely apt that Atwood has written a soon-to-be-published sequel to this novel called “The Testaments”. Sadly, it feels like there’s no better time to return to the fictional world of Gilead to gain a different perspective on the current state of the world. Since I reread this novel partly as preparation for reading this forthcoming sequel I tried to pay attention to how its story might continue. The tight embargo on “The Testaments” means all we know about this second book is that it takes place fifteen years after Offred leaves for an unknown destination and that it’s narrated from the perspectives of three different women from Gilead. The imagery of the new cover includes a green smock so I wonder if one or all of these perspectives will be narrated by Marthas who are older infertile domestic servants within Gilead that only dress in green. I’m also hoping this new tale will give some more clues about Offred’s real identity since we never know her true name or what ultimately became of her.

Rereading this novel also gave me a renewed appreciation for the beauty of Atwood’s prose in her use of metaphorical language such as when Offred describes an egg or the subtly of her psychological portrayal as Offred becomes more attuned to the mechanisms behind her oppression. While I’ve always been a fan of Atwood I haven’t read much of her fiction in the past several years except her novel “Hag-Seed” which is a fascinating remix of “The Tempest”. But this rereading also reminded me how richly imaginative and wild Atwood’s fiction can get. I was also surprised how gripping I found it though I already knew the plot. Each twist and revelation in Offred’s story felt fresh because we’re so closely rooted in the tense psychological reality of her experience. It’s made me even more eager to know what happens next!