I can’t think of any other literary novel that has had such a build-up prior to its release. Details of the story were shrouded in secrecy and its shortlisting on this year’s Booker Prize all contributed to an anticipation which culminated in a midnight release of the book this week and a live interview with Atwood that was streamed to over 1,300 cinemas around the world. I have to admit, I jumped right on board the hype train and read the novel over the course of a day. Personally, I was especially excited to see how the story would continue 15 years in the future after Offred’s final scene and discover more about Gilead’s downfall because I reread “The Handmaid’s Tale” so recently. In “The Testaments” we get a lot more about the workings of this dystopian society because it’s narrated from three different perspectives who all have unique views and access to different layers of this totalitarian state. In doing so, Atwood offers further perceptive critiques on the nature of patriarchal society and presents moving psychological insights into how people survive (or perish) within oppressive regimes. I have to say the way the central characters’ stories come together is a bit forced and the plot is somewhat predictable. Nevertheless, it’s a continuously engaging and gripping experience reading this book.

Central to the tale is Aunt Lydia who appeared in the original novel in Offred’s memories as an imposing tyrant who trains her as a handmaid. In “The Testaments” we get Lydia’s secret account that she stows in her private library describing her journey from pre-Gilead times as a left-leaning judge to her imprisonment, torture and eventual position as one of the architects of Gilead society. She’s a complex and difficult character who hoards secrets as a means of maintaining her power: “I’ve made it my business to know where the bodies are buried.” Lydia experienced a traumatic wakeup call as she witnessed a democratic American society shift to a puritanical totalitarian state: “People became frightened. Then they became angry. The absence of viable remedies. The search for someone to blame. Why did I think it would nonetheless be business as usual? Because we’d been hearing these things for so long I suppose. You don’t believe the sky is falling until a chunk of it falls on you.” Rather than perish she proved her durability as a survivor and someone willing to compromise her morals in order to persist. She also takes pleasure in her power and position when denouncing her enemies or extinguishing those she views as weak: “I judged. I pronounced the sentence.” I appreciate the way Atwood depicts Lydia as an oppressor, but someone who is nonetheless sympathetic in her desire to live no matter the cost and becomes entombed in a perilous loneliness: “Having no friends, I must make due with enemies.”

The other two narrators are much younger and were born in Gilead so have no knowledge of a world without it. But they live on opposite sides of the border. Agnes lives in a privileged family within Gilead. She’s raised as a true believer and reared to become the high class wife of a commander. Daisy lives in the neighbouring democratic state of Canada and becomes involved with anti-Gilead protests. Both these girls experience severe disruptions when their intended paths in life abruptly change due to larger events and secrets are unearthed about their true origins. While their journeys are compelling the way Atwood brings together her three narrators’ stories relies too heavily on chance and convenience. The girls also perhaps serve too neatly as optimistic perspectives in contrast to Aunt Lydia’s position of corruption and vengeance. They are innocent as Agnes explains “We’d been protected… I’m afraid we did not fully appreciate the extent to which those of Aunt Lydia’s generation had been hardened in the fire. They had a ruthlessness about them that we lacked.”

Something I found really powerful about Agnes’ story is her friendship with a girl named Becka. While the other girls in their class enthusiastically embrace the idea of marrying a commander for the privileges such a position will bestow upon them, Becka adamantly refuses to marry because of her fear of sexual contact with men. It’s clear she’s experienced some unconfessed trauma, but Agnes doesn’t feel like she can discuss this with Becka because of her fear of the associated repercussions. While “The Handmaid’s Tale” meaningfully depicted the way women hesitate to be emotionally open for fear of being denounced, “The Testaments” further develops the way in which state pressure can reinforce these silences and prevent close friendships.

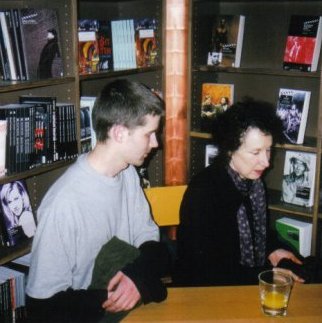

Atwood on the evening of the launch of The Testaments

More than the circumstances of the stories being portrayed, I probably felt more moved by the parallels between events “The Testaments” depicts and instances in the real world. Atwood has famously stated how “The Handmaid’s Tale” doesn’t portray anything which hasn’t already happened in human history and the same is true for this novel: governments “temporarily” take away citizens’ rights in a move towards totalitarianism; children are stolen from their birth parents and allocated to state-sanctioned couples; men use their positions of power to sexually abuse young females and sacred texts are wilfully misinterpreted for sinister motives. It’s all depressingly familiar and current. These universal themes about the deleterious effects of corrupt patriarchal governments reinforce the enduring power of “The Handmaid’s Tale” and show why it’s become such a well-known part of popular culture. That Atwood feels the need to further examine the machinations of such a brutal regime and the moral conundrums these societal shifts present to individuals feels prescient.

Atwood has stated that one of the reasons it’s taken her so long to write a sequel to her famous novel from 1985 is that it took a long time to decide upon a structure and choice of narrators. I can’t imagine any better trio of narrators to continue Gilead’s tale than the ones she’s chosen. But strangely I wish she’d concentrated less on building such a tightly woven plot and neat conclusions for her characters. Rather than being taken to the centre of Gilead I’d have been content to dwell in the periphery with characters whose lives have hardened from living in such a restrictive society. Part of the power of “The Handmaid’s Tale” was in the necessarily restricted view and understanding Offred had of her surroundings. It’s what heightened the horror because this experience more accurately reflects our own. This new novel will satisfy the curiosity many Atwood fans who want to know what happened next, but at the expense of that terrifying ignorance we felt dwelling in the restrictive cowl of a handmaid’s bonnet.