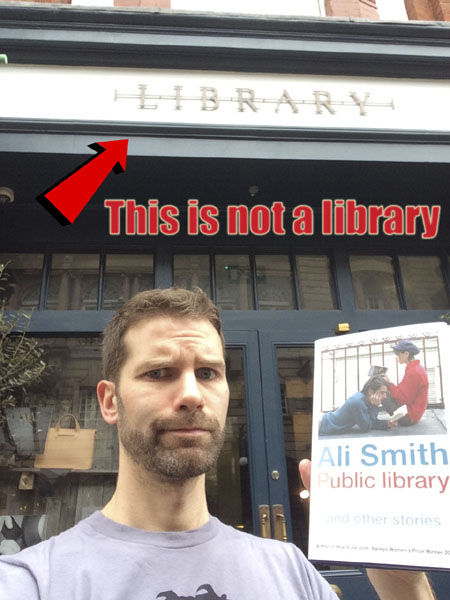

We’re getting to a point where a library isn’t a library anymore. As Ali Smith humorously discovers in the opening of her new book of short stories, a building in central London marked library is now more likely to be a private members’ club that is focused on lists of cocktails rather than sharing literature. Despite the 1964 Public Libraries and Museums Act in the UK which states local councils are under a legal obligation to provide library services, over ten percent of the libraries in this country are under threat of closure. We’re told there isn’t enough money for libraries; we’re told banks need the money more. Campaigns have been afoot across the country to save these vital cultural institutions. This book is a way of weaving together the way in which literature is a physical part of our everyday lives. Interspersed with the stylistically-daring short stories in this collection are testimonies about our personal relationships with libraries by people ranging from authors such as Helen Oyeyemi, Kate Atkinson, Kamila Shamsie, Miriam Toews and Jackie Kay to fabulous, passionate people in publishing like Anna Ridley and Anna James. Libraries make authors and publishers who make more books which in turn make more libraries and authors and publishers. Ali Smith’s “Public Library” is a vibrant, loving tribute to libraries, our passion for books and how they are an integral part of our communities.

In several stories there are seemingly closed systems which the characters struggle against. One narrator tries to convince a newspaper that he’s still alive after they publish a false story about his death – twice! Another narrator argues with a credit card company that she never purchased a plane ticket which has appeared on her statement. One narrator speaks on the phone with a doctor’s office about the tree which is growing out of her/his chest until the important things being said fade into the background and there is just the beauty of the blossoming tree. There is a lot of drifting away from the trivial everydayness of the world and rigid ways in which people can limit language. Drawn by thoughts of poetry, fiction and song characters walk away from important meetings, important people, important places. Literature draws them into the imagination, into the unknown because you never know what you’ll find between the covers of a book. If you crack a book open there may even be poetry sewn into its spine. People lose themselves in books (as the title of one story states) to take them to “The art of elsewhere.”

As clever and as sophisticated as Ali Smith’s stories are, they always pay close attention to the importance of human relationships so the characters feel immediate and real. They have arguments, misunderstandings, money worries and jealousy. The voices of these characters shine through. It feels like it could be Smith herself stating her writing mission when one character remarks: “I want it to be about voice, not image, because everything’s image these days and I have a feeling we’re getting further and further away from human voices.” It’s amazing the way Smith is able to make her characters feel so familiar even though in many cases the protagonists remain nameless and sometimes we don’t even know their gender. They speak intimately about grief, fear and love in a way that draws you into their experience and you can absorb it into your own life.

There is also so much lively humour in this book. There’s confusion between D.H. Lawrence and DHL “The deliveryman.” There is a boy/girl who pleads to pay for a new toaster with flowers. There is a character whose partner is so engaged with Katherine Mansfield’s life and writing that she becomes like an ex-wife between them. There is wordplay: it’s explained that a girl whose father is in and out of prison “from time to time, did time.” It’s as if Ali Smith can peel open words to consider their origins and the way they are commonly used to then blend them into her narrative and conversations between characters to give them whole new meanings.

Most importantly, “Public Library” shows the way literature is a part of our consciousness, shaping and moulding who we are and influencing our actions. It’s not abstract or separate from our everyday lives. It’s physical. Smith shows that long dead authors themselves are still a solid presence in the world. D.H. Lawrence’s ashes could be scattered anywhere. Remnants of Katharine Mansfield are a part of the wings of planes. The records and recorders of our culture don’t hang in an ethereal way above our lives; we interact with them every day. These stories make the world feel refreshing and new. They draw you back into life. They make you want to run to your nearest library.

Since this book is filled with so many moving personal statements about what libraries mean to us, I’m going to give my own…

In 1999, I left my small college in Vermont (which is close to a town called Norwich) in order to live for several months in Norwich, England. I went as part of a study abroad programme, but really I made the hasty decision to leave the US after the breakdown of a relationship. What can be more satisfying than casually mentioning to your former lover who has left you: “Oh, didn’t you know? I’m moving to England.”

Arriving at the stark concrete University of East Anglia campus which is surrounded by fields with rabbits and Shetland ponies, I was suddenly on my own and I had no idea what I was doing there. I found out there was something called a Union Pub & Bar where members of my student residential building took me to drink and socialize. I didn’t like to drink (at that time) and I could never hear what people were saying over the loud music. Soon I made a hasty retreat to the large library on campus.

There on the quiet floors filled with books my friend Carolyn and I played games like “who can find the gaudiest-looking book in the library” and there she introduced me to the first book I read by Joyce Carol Oates who would go on to be my favourite author. There I discovered a much-battered old edition of a book containing two holograph drafts of Virginia Woolf’s novel “The Waves” where you can see copies of the actual words crossed-out and additions she made in the margins when writing it. There I watched a black and white VHS recording of an interview between Lorna Sage, Malcolm Bradbury and Iris Murdoch who all smoked throughout the discussion making the screen appear like a hazy intellectual fantasy set in heaven.

There I sat in the library one dreary lonely afternoon taking notes and plotting the key points of a literary graph I planned to mark the years of key publications by modernist authors so I could physically see where they intersected. It wasn’t a class project – just a fun thing to put on the wall in my little dorm room. I was excited to find that T.S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland” came out the same year as Virginia Woolf’s “Jacob’s Room” and the same year as D.H. Lawrence’s “Aaron’s Rod” and the same year as James Joyce’s “Ulysses.” And there, surrounded by my reference books and poster board and ruler and pencils and mess of notes, a man who I’d go on to live with and love for the next sixteen years approached me and said with an amused grin, “Hi, aren’t we in the same creative writing class? What on Earth are you doing?”