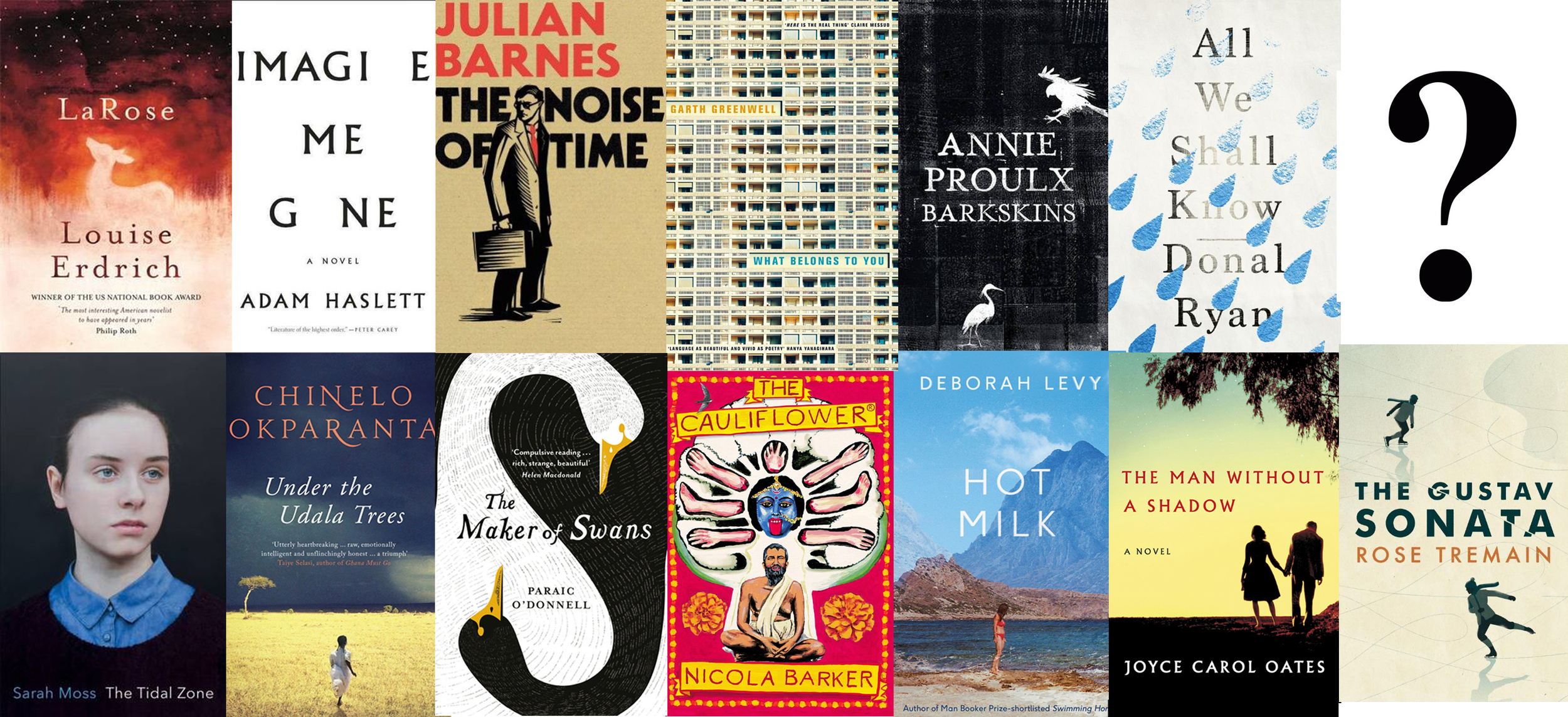

Adam Haslett is a writer who powerfully conveys the full complexity and heartrending challenges of family relations. I read the story 'Notes to My Biographer' in his debut book “You Are Not a Stranger Here” years ago, but the strained and affecting father-son relationship it portrayed still haunts me. His first novel “Union Atlantic” powerfully explores recent issues of social and economic strife at both larger and more intimate levels. The power of his writing lies more often in what isn't said than what is overtly stated. That's certainly true in this his second novel “Imagine Me Gone” about the infinite difficulties and enduring love found in family life. Dealing with issues such as depression, prescription drug abuse and sexuality in a disarmingly refreshing way, Haslett shows the tender way people care and love one another under difficult circumstances.

An Englishman John meets American Margaret at a party and the romance that ensues is troubled by typical problems such as establishing secure work and the question of where to settle down. However, it becomes alarmingly clear that John is troubled by mental health issues. Nevertheless they marry and have three children. Over a number of years the “beast” which psychologically hounds John makes its presence felt. As the eldest son Michael grows he too struggles with psychological issues that an American doctor treats with doses of medication which steadily increase in quantity. Meanwhile the family comes under increasing financial pressure as medical bills mount up. Over a number of years the family split apart and come back together in an effort to support one another.

At times Haslett's writing almost has the feel of a documentary filmmaker (like Frederick Wiseman) for how he conveys the way people can verbally spill out their lives. There is a certain frantic energy some have for talking endlessly in a self-justified way trying to convince whoever is listening of their point of view. In one scene Michael is speaking to his sister Celia on the phone about a relationship crisis which both Celia (and the reader) realizes is hopeless. He doesn't want advice. It's as if by narrating every detail of the situation over and over Michael can control it, but what he's not talking about are underlying issues that motivate his clinging desire. I've had many conversations like this with people and it's like witnessing a barrage of words that cover hidden pain. It's commendable how realistically Haslett recreates this in his novel.

One of the most moving and beautiful passages of the book comes early on when John is reading to his youngest son Alec. Haslett writes that “Alec will be quieted to the point of trance, by the story, but also because his father’s attention is pouring over him, and only him, like the air of heaven.” I love how this conveys that its not necessarily the words that matter but the intimate act of storytelling creates an intimate bond which is very special. It almost brought me to tears as it made me recall moments in my childhood when my father read to me at bedtime.

Alec grows to be a gay man who ultimately struggles with intimacy as many young men do when ensconced in a gay culture focused so much on superficial appearances and the perfect erotic highs promised in porn. It's striking how Alec's issue is not with finding acceptance within his family, but with confronting his own difficulty in forming substantial emotional relations with men he's sexually involved with. He cruises men not so much for sexual release but “To matter, and know that you mattered.” It's a bracing and refreshing way of showing the issues that gay men face. Haslett also shows the same sensitivity when showing Margaret's struggle with her changing looks and being single as she grows older where she states: “It took me a while to understand the subtlety of it, the way invisibility works at my age.” There is an awareness of how women can be made to feel they are worth less as beauty fades and how this makes people readjust how they deal with others socially.

At one point Michael get's the song 'Temptation' by New Order endlessly stuck in his head.

Haslett's innovative narrative techniques prevent the tone of his story from ever becoming maudlin. Each member of the family is given sections which are narrated in the first person, but where John speaks directly and powerfully about his internal struggle with depression “The monster you lie with is your own. The struggle is endlessly private” his son Michael conveys the pain of his issues in an entirely different way. For instance, he describes a family therapy session as if he were delivering a military report or when answering questions on a forebearance form to a loan company he'll quote Proust and lecture about the legacy of slavery. In an incredibly striking section of the novel Michael writes letters to his aunt describing the family's boat journey from the US to Europe where the trip surreally devolves into a dystopian cruise ride to hell with Donna Summer performing her hits during passengers' enforced exercise. What's extraordinary is that these passages manage to be both comical as well as tremendously touching for the way they effectively convey Michael's frustration and disillusionment with the society around him as his wellbeing spirals downward.

A trip to Maine where brothers Michael and Alec stay at the house their family vacationed at in their youth provides a frame for the novel. At the start something goes horribly wrong there and its only after learning about the complex inner life of this family that the reader fully understands the problems that contribute to the brothers' dilemma. This also creates an element of suspense as its only revealed at the end what brings their stay to a crisis point. Haslett is a writer that possesses a powerful narrative style and a complex understanding of the subtleties of human relationships. “Imagine Me Gone” is a stunningly heartfelt account of family life.