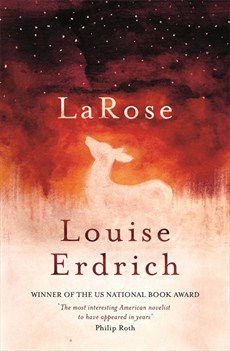

It's difficult not to fall in love with a novel so firmly rooted in a love of books. Tookie, the protagonist of “The Sentence”, works in a Minneapolis bookshop. She's established a relatively stable life after extending her teenage habits into her 30s and serving time in prison for a bizarre crime. But her peaceful days are disturbed when a deceased customer named Flora starts haunting the bookshop. The specific sounds and messy habits of this woman were well known to Tookie so she's immediately able to identify whose invisible presence is browsing the bookshelves. Flora was a well-meaning and open-hearted individual who frequently spent time in the shop, but she possessed the “wannabe” characteristic of a white woman who likes to imagine she possesses Native American heritage. While raising a problematic attitude connected with liberal white society, this is also a playful and ingenious narrative twist on a familiar outdated trope of American storytelling which frequently invoked Indigenous stereotypes for the sake of comedy or horror – i.e. the common reference of “Indian burial grounds” in ghost stories. Tookie also frequently pokes fun at the pointed reasons which bring customers into the shop. Not only does this novel reference a lot of recent literature from Ferrante's “The Days of Abandonment” to “Black Leopard, Red Wolf” but it also includes idiosyncratic lists of books from 'Short Perfect Novels' to 'Tookie's Pandemic Reading'. In a way, this makes the experience of reading Erdrich's novel feel simply like a conversation with a fellow book lover.

There's an easygoing familiarity to the characters whose daily trials we follow alongside Tookie's supernatural storyline. She comes into possession of the book Flora died reading and it might be cursed. The process of dispelling Flora's spectral presence is connected to this artefact which provides a new view of Indigenous history. However, this central part of the narrative becomes more of a side note when world events take over. Erdrich has stated in interviews how she wrote this novel “in real time” so when the pandemic hits it dominates the story as does the shocking occurrence of George Floyd's murder and the protests which ensue. This makes the narrative feel somewhat like a jostling ride or a lockdown diary. Other novels from Ali Smith's “Summer” to Sarah Moss' “The Fell” have been based around the pandemic, but incorporated the fact of it more intrinsically into the story. In Erdrich's novel it jumps in abruptly. Though part of me wished for more cohesion and a neater arc I appreciated how this made a suitably open-ended tale which captures the ongoing uncertain nature of our times. It also carries on political themes which can be seen throughout the novel and shows how history is an ongoing story. I guess that's another reason why this book feels more like it's opening a dialogue rather than creating a self enclosed narrative. It makes me highly conscious of the fact that any novel that begins in late 2019 will have to wrestle with the fact of the coming pandemic or comment upon it in some way.