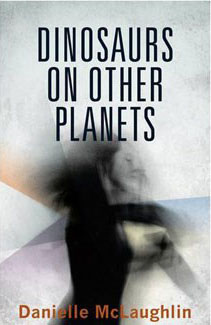

When I read Danielle McLaughlin's debut book of short stories “Dinosaurs on Other Planets” I knew this was an author to watch. Her ability to capture the nuances of our psychological reality and complex relationships in fiction is extraordinary. McLaughlin's talent has been confirmed by being awarded a Windham Campbell Prize and the Sunday Times Audible Short Story Award in 2019 as well as numerous other literary awards. So her first novel comes with a lot of anticipation.

At its heart, “The Art of Falling” is about a seemingly ordinary woman named Nessa whose busy days are filled with her work at an art gallery and caring for her family: husband Philip whose ambitious property development business has fallen on hard times in the wake of the devastating Irish property bubble and teenage daughter Jennifer who is growing secretive and difficult. Yet, amidst juggling gallery lectures and shopping for food to make the family dinner, Nessa grows increasingly aware of how fragile her secure reality has become. Her marriage is still recovering from the recent discovery that Philip was having an affair. More inconvenient truths from the past soon emerge. An eccentric woman publicly asserts that she is the true creator of a famous sculpture that's the centrepiece of an exhibit Nessa is curating. Also, the son of Nessa's long-deceased friend Amy visits the area seeking to learn more about his mother's life. These factors tip Nessa's world into chaos as she scrambles to keep things together and she must question whether buried truths should remain so. These dilemmas create an emotional pressure which is intensely felt and the complex meaning of this story gradually unfolds as the facts are revealed.

One of the things about getting older is that our versions of the past become solidified within our own self-justification and egocentric certainty. Anything that challenges this is often met with suspicion and hostility. Therefore it's moving the way Nessa must accept her own role in perpetuating mythologies which have emerged regarding an artist's career and her friend whose life was tragically cut short. McLaughlin's story raises many intriguing questions. To what degree are facts manipulated to serve a common narrative? What does our subjective experience do to bend the truth? Does excavating certain truths about the past enhance our reality or disrupt it? How much forgiveness is necessary if we want to honestly know what happened in the past? This novel inspires a deep reckoning with one's personal history in a way similar to Julian Barnes' “The Sense of an Ending”. It made me reflect on my own past and how much I have psychologically tidied away to serve my own purposes. What Nessa's tale beautifully shows is that this is a very human trait and we need to be careful about how we manage collective and personal memory.

I admire how McLaughlin is able to raise all these probing questions gradually so they primarily emerge and continue to meaningfully linger after the story finishes. While reading this novel I got so involved with the sympathetic details of Nessa's life and the mysteries of the plot as it unfolded. Like Anne Tyler, McLaughlin has a way of making the everyday wonderfully engaging. This made reading it a very pleasurable experience. There are details which have stuck in my imagination such as the central sculpture which was made with a material that causes it to slowly disintegrate over time. The artist might have been done this purposefully or not, but the nature of this artwork raises a point about what should remain permanent. By encoding personal history into a certain narrative we're limiting the truth about how complex the experience of living really is, yet it's a necessary part of forming identity. “The Art of Falling” shows how the messiness of these dilemmas and questions make being human both beautiful and eternally troubling.