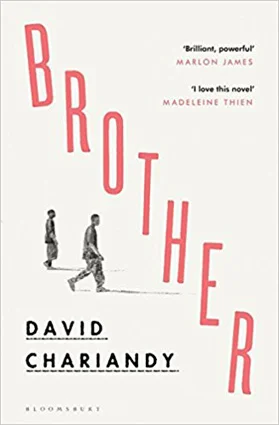

It's difficult to capture the slow-burning sense of alienation that someone can feel within family life, but in “Brother” David Chariandy powerfully depicts the story of a working class mother and her two sons in a way that gives a fully rounded sense of this. Michael lives with his grieving and fragile mother in a tower block in Scarborough, a district of Toronto with a high immigrant population. He still sleeps in the bunk bed of his childhood, but now the top bunk is empty and gradually we discover what happened to his absent brother Francis over the course of the novel. Michael struggles to get enough shift work at his low-paid job and spends the bulk of his time caring for his mentally-precarious mother. They are both haunted by a sense of loss and penned in by their circumstances. What's so beautiful about Chariandy's narrative is how he subtly captures the sense of a family who essentially loves and cares for each other, but whose status as West Indian immigrants has made them into perpetual outsiders and these internalized feelings make them unknown even to each other.

Michael relates the story of growing up in the shadow of his old brother Francis who is more socially adept and desirable. I found it particularly heartbreaking how Michael never really feels inadequate until it's pointed out to him by Francis coaching him in how to act or dress or when someone in their circle expresses resentment about Michael's presence. This builds to a sense of self consciousness that's formed from being continuously reminded that he doesn't fit in. Yet there are aspects of Francis' identity which never allow him to fully fit in either and parts of himself he perpetually hides. Most of all the boys economic and ethnic status contribute to their slow realization that they can never fully feel a part of the community that they've grown up in. There's such a striking moment early on in the novel when the brothers watch a television through a shop window. It's showing news report about street violence and while they're watching they can see their own reflections superimposed over the screen. This gives a powerful, haunting sense of how they are trapped in a community troubled by poverty and gang wars.

The family's neighbour Aisha was able to progress onto university, but she returns when her father dies and subsequently helps Michael care for his mother. Unfortunately for Michael and many other people in this immigrant community there are few ways to progress into a life with economic security or escape the perpetual sense of disenfranchisement. At one point in Michael's life he realizes “We were losers and neighbourhood schemers. We were the children of the help, without futures. We were, none of us, what our parents wanted us to be. We were not what any other adults wanted us to be. We were nobodies, or else, somehow, a city.” The novel gradually unfurls the multiple ways this comes to define Michael's life and the tragic way he doesn't fully understand his brother until he's lost.