What place does art hold in our day to day lives? That's one of the questions at the centre of Sara Baume's second novel. Frankie is a twenty-five year old woman who has left her rented apartment in Dublin after studying art and working in a gallery. Finding it impossible to integrate into a working and social life as her uni friends have and concluding that “The world is wrong, and I am too small to fix it, too self-absorbed”, she retreats to her late grandmother's rural bungalow. She endeavours to create art on a daily basis and continuously quizzes herself finding thematic connections between incidents in her life and specific pieces of art. Her family come to visit and hover close by as they are concerned about her mental health. Frankie experiences depression and she becomes increasingly isolated because of her prickly demeanour. The author's debut novel “Spill Simmer Falter Wither” recounted the reclusive life of a man and his dog at the fringes of society. With this inventive and fascinating new novel Baume proves that she is the master of describing the intense poignancy of solitude within a noise-drenched world.

One of the things that makes Frankie so relatable is the way she internalizes snippets of recent news or things she sees in films. There are popular incidents from recent memory she notes such as published aerial photos of the last “uncontacted” tribe in the world and news of the Malaysia Airlines flight which disappeared. These incidents take on a special significance for her speaking to how she is disconnected from larger society. Also, she recounts watching Herzog's documentary Encounters at the End of the World which records the filmmaker's time with scientists in Antartica. There is a poignant moment towards the end of the film where a “deranged” penguin inexplicably wanders away from his colony to the mountains, isolation and death. Frankie seems to wonder if she is like this lone individual, an aberration of her civilization destined for loneliness. This reminded me strongly of Jessie Greengrass' short stories for their similar philosophical contemplation about the meaning of solitude within an icy landscape.

Each chapter recounts and reproduces the photographs Frankie takes in the countryside. She takes photos of dead birds and small mammals she encounters to reflect “the immense poignancy of how, in the course of ordinary life, we only get to look closely at the sublime once it has dropped to the ditch, once the maggots have already arrived at work.” It's somewhat shocking as a reader to be confronted with these photos of dead animals to consider their sentiment and macabre beauty. They are things which most people would turn away from if they encountered them on a ramble through nature. But Frankie sees significance in these and many other things she comes across, considering how they might be artistic expressions of deeper ideas about the state of existence.

It may sound like this novel is too ponderous or fixated on the grim facts of life, but there are also touches of dark humour that relieve it from being too bogged in seriousness. Frankie's perspective can turn surprisingly funny especially when she thinks about religion. At one time she recalls a priest she knew who seemed so “priestly” it was impossible to imagine him as human under his cassock and instead being like a Russian doll of clerical clothing. In another scene she gets her hair cut and reflects how the experience de-personalizes us: “Here in the hairdresser’s, we are all ill-defined, inchoate. We are all but ankles and shoes, wet necks and wet foreheads.” The usual conversational chatter the hairdresser tries to make is quickly rebuffed by Frankie. Her refusal to engage in social pleasantries often has a humorous effect for her brutal honesty when “people don’t like it when you say real things”, but it's also unsettling for how cruel she can be to a doctor at a mental health centre or to her own mother calling to wish her happy birthday.

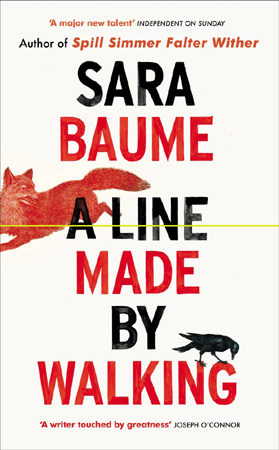

Frankie sees in Van Gogh's Wheatfield with Crows "An angry, churning sky, tall yellow stalks, a grass-green and mud-brown path cutting through the stalks, tapering into the distance; a line made by walking."

There is something refreshingly inventive about Baume's writing which resists using traditional metaphors or descriptions. A pet peeve of mine is reading overused creative writing tricks that imbue objects with sensory feelings like calling a sponge “lemon yellow.” However, Baume describes a Christian leaflet that Frankie is given as “stomach-bile yellow” and a rising sun as a “a prickly auburn mound.” These meaningfully reflect her character's state of mind as well as showing a humorous contempt for trying to invoke pleasant imagery. Frankie also forthrightly declares herself outside the narrative of a novel or film stating “The weather doesn’t match my mood; the script never supplies itself, nor is the score composed to instruct my feelings, and there isn’t an audience.” This goes against the prevailing feeling of our age that we live our lives as if we're the stars of our own reality shows or that we're in a book or film where the sky is imbued with poetic descriptions and music accompanies the emotion of our encounters. Of course, ironically, Frankie can't escape the fact that she is a character in a novel: there are emotive descriptions of the sky and Frankie listens to Bjork on high volume while she's travelling.

Frankie's actions are extreme as she's experiencing a severe form of depression, but her thought process and inclinations are highly relatable. The decision to engage with or remove yourself from society is something many people wrestle with on a daily basis and we can shelter our inner being in a multitude of ways. The question of whether isolation is a more honest form of living or a surefire way to descend into madness is meaningfully explored in this novel and the recent novel “Beast” by Paul Kingsnorth. What's overwhelmingly touching about Frankie's view is her steadfast belief in the redeeming influence of art over any institutionalized belief system like psychiatry or religion. She feels “art remains the closest I have ever come to witnessing magic.” So she clings to this belief in the power of art to connect her to humanity and raise her out of the mire of existence no matter how deeply alone she becomes.