I've been wanting to read this novel since it was published earlier this year. It's interesting getting to it now so soon after reading "Fates and Furies" because both novels are concerned with the way women's points of view are suppressed in narratives, but they have very different approaches. In "The Vegetarian" the novel begins with a conventional man's perspective complaining how his unremarkable wife Yeong-hye suddenly became a vegetarian, thus passively disrupting their blandly ordered existence. His cruelly reductive opinions about his wife suggest that she is especially unspecial: “She really had been the most ordinary woman in the world” but his perspective is interspersed with short intense italicised passages revealing this wife's inner monologue. Like a modern day Bartleby, by resisting to observe convention and quietly refusing to do what's expected of her, the wife's family become incensed and her life completely changes. What follows is a novel of strange beauty as a woman's strong inner-life is gradually revealed and the constrictive society around her is forced to acknowledge the power of her independent perspective.

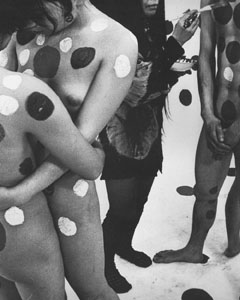

An artist is inspired by the radical and colourful artist Yayoi Kusama to paint nude bodies with flowers.

In some ways this is a surreal story where a woman believes that she's gradually transforming into a plant. The reasons for this transformation are very different from the narrator in Ali Smith's story 'The beholder' in “Public Library” who experiences a real blossoming of branches and flowers out of her/his body. At the same time “The Vegetarian” is a brutally realistic tale about the long-term effects of child abuse and the diminishment of women in society. Her transition begins in earnest when in the second section her sister's artist husband creates a video installation centred on painting flowers on Yeong-hye's naked body. This is a project bourne out of his sexual obsession and was in part inspired by the artist Yayoi Kusama who colourfully painted her subjects bodies and let them interact with each other. The brother-in-law's project is more sinister as his secret desire to possess and have sex with Yeong-hye builds to a terrifying scene.

The novel's focus eventually shifts to her sister In-hye's perspective and concerns Yeong-hye's being sectioned after her total mental breakdown. Here the story becomes much more intimate and confessional. The spectre of an abusive father looms large so that Yeong-hye's transition from submissive wife to outright rebellion seems entirely logical. Normality is inverted because beneath the veneer of civilization there is a world of hidden pain. So it feels that “sometimes it's the tranquil streets filled with so-called 'normal' people that end up seeming strange.” I admired how the novel gradually builds a complex portrait of a woman's inner life created entirely from the points of view of the people around her. The reader is given hints and suggestions of a radically different form of consciousness that wants to rapidly evolve to a more organic existence, yet she's suppressed by the social world that uses limited terms to define her life. “The Vegetarian” is a novel of rebellion, hope and rare passion.