I always admire a novel that is wise enough to raise questions about the central dilemmas of our lives without feeling the need to give definitive answers. It shows a mature understanding for how we really stumble blindly through it all though we pretend that we can see. To me it feels there is no greater mystery than our relationships to each other. How do we really see the people we love? As they are or as we believe them to be? How do our memories of them colour our feelings towards them? How do they really feel about us? In what way do our own feelings inform what we think others think about us? “All the Days and Nights” challenges us to consider these queries with the story of aging ailing artist Anna and her younger husband John who has left her for good.

Anna narrates the novel directly to John recalling their life together and the way his image has been made famous in the multiple portraits of him she’s produced. In their New England home she struggles to produce a new painting of her friend and agent Ben who has descended upon her because she has broken off communication with the outside. She has a combative relationship with her assistant, fellow artist and sometimes muse Vishni – a bond that feels as spiky and co-dependant as that which existed between Virginia Woolf and her cook Sophie Farrell. The difficult relationships between the characters are depicted evocatively with pointed conversations and emotionally-jarring reminiscences.

It’s admirable the way that Govinden writes of the relationship between Anna and John as being totally unique. It seems an obvious thing; after all, every relationship is unique. But we so often affix the labels of marriage or friends or lovers or parents to the people we know and in doing so reduce the complexity of these bonds. So much of what we feel for each other lies in between these notions and mutates as we grow older with each other – yet the labels so often remain the same. Govinden breaks through these restrictions. He conveyed this ambiguity of feeling beautifully in his depiction of another couple in his previous novel (which I reviewed here last year) “Black Bread, White Beer” as well. To Anna and John the word married seems something of a farcical label affixed for convenience rather than as an accurate way of describing the deep bond that they share.

The novel beautifully asserts the central mission of the artist: to memorialize what is ephemeral and fleeting. For Anna the process of creating “is an ongoing act of revelation” giving to her an understanding of her subjects and also fixing an interpretation of them which memory by itself cannot. Anna’s attempts to capture John have resulted in multiple portraits which catalogue their life together and the feelings that have passed between them. Now John is on a mission to discover what these really mean while leaving Anna behind. He also leaves actual photos of them together which Anna thinks are “a happiness you [John] no longer wish to remember.” This all sounds rather mournful and tragic. But I think that rather than destroying what remains of their relationship by leaving, John’s mission is more a desperate act to reclaim their life together and better understand how Anna really sees him.

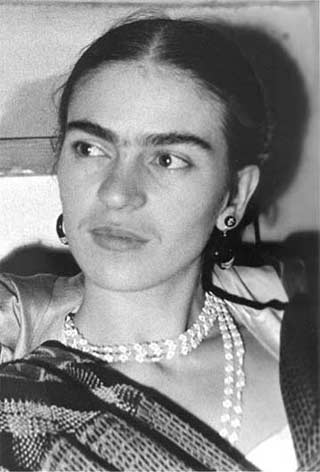

novel's epigraph by Frida Kahlo "I leave you my portrait so that you will have my presence all the days and nights that I am away from you."

Memories are planted throughout this novel like questions which exist only to garner other questions. Rather than acting as touchstones to arrive at neat reconciliations and resolutions, Anna and John’s recollections make them grapple more for an understanding of the full complexity of what has passed. It’s observed that memories take on a ferocious charm in the way they hound the mind in our advanced years: “The torturer and salve that memory becomes in old age.” The characters noble method of dealing with this accumulation of experience is to create because art is also what we produce and consume to make sense of the impossible joys and tragedies of life. For Anna: “This is the only way that I can understand things, using order and method to make sense of chaos” It’s an inspiring mission, but also a fervently possessive one as Anna also acknowledges “something to be shared inevitably comes from a selfish hand.”

This short, powerful novel depicts a relationship so skilfully condensed that it blossoms in the reader’s mind suggesting experience far beyond what the pages contain. It expounds upon the complex mission for creating art and the transformative experience of viewing art. Govinden shows his characters’ quest to transcend the detail of life and reach for a better understanding of its meaning. It’s a book where certain images and moments really linger in the mind. Since it’s under 200 pages if you can spare a morning and afternoon to devote to reading it in full I’d recommend it. This way you can really immerse yourself in the cumulative power of the prose and swallow this moving story in one greedy gulp.