When trying to show how most of our lives are lived on the surface while all sorts of wild desires and fantasies remain hidden inside us, traditional fiction usually only shows tiny hints of this multi-layered reality in the thoughts of characters and their dramatic actions. In fairy tales this sublimated fear and lust explodes like a geyser. Although the more traditional kinds of these tales are usually sugared for children, Kirsty Logan has written stories which are decidedly for adults due to their frankness of feeling and the complexity of their ideas.

Some stories in this short, powerful book play upon tales we’re already familiar with giving a different perspective or reconfiguring their limited morality. In ‘Matryoshka’ when the “villain” sister ends up alone while the maid she ardently desires ultimately gets to wear the pretty shoes and win the prince it feels like the most devastating kind of romantic tragedy. When the narrator of ‘Witch’ stumbles upon the notorious feared woman who lives in a hut in the woods she discovers that her ostracism from society is of her own making and her alternative lifestyle is far preferable from living with the mainstream. In ‘All the Better to Eat You With’ which is a very short tale told all in dialogue the meaning stretches out to encompass more universal philosophical ideas about the survival struggle of all species which are divided between hunters and the hunted. Characters speaking collectively in the story ‘Underskirts’ emphatically declare themselves as outside of traditional time-honoured stories “We were not the stepmothers from fairy tales” as they sell their daughters into a salacious wealthy household out of financial necessity. The title character of ‘Sleeping Beauty’ is cast in a present day starkly realistic setting. In this story the unfolding narrative of a girl who suffered sexual assault after being drugged at a party is ingeniously told backwards so that the hard realism of the event strikes the reader like a hammer. It also meaningfully shows the psychology of a young woman who is trying to forget the event rather than go through the difficulty of reporting it. Far from frivolous, these twists on familiar fantasies are serious stuff.

These imaginative stories are also very playful, funny and sexy. Some are set in grand, old-world settings like a country estate where the lady of the house is known to take in select local country girls for indulgent happenings. Still others take place in the recognizable gritty reality of the present where couples are separated through the necessity of keeping self-sustaining work or struggle with the difficulty of pregnancy. Take for instance, this line from ‘A Skull of Saints’: “People are more than DNA, she knows, but if she could feel their child from her insides, know him with her own flesh the way that Hope does, it would be better. It would make sense. He would feel more like her own; he would be more than just an idea.” This story explores what the real significance of empathy and familial relationships in the way people relate to and think about each other. Yet these stories cleverly bend what’s real and stretch into the fantastic so that children grow antlers or tiger tails in ‘Una and Coll are not Friends.’ The story is told in their voices which sound like any adolescent you might overhear on the street. But the physical imposition of animal appendages makes a powerful statement about the meaning of diversity and divisions which can occur within minority groups. In the story ‘Origami’ a woman waits for her husband who is ceaselessly delayed by work and spends her time making a man out of folded paper. With this oddball detail it makes a powerful comment on the sense of complex isolation one can feel within a committed relationship: “She wasn’t lonely, she was victorious.”

Most of these stories squeeze at the prickly heart of love to make fresh revelatory statements about the meaning of relationships. The title story includes a woman who must rent a heart to begin new romances. In another story a woman takes a companion of a coin operated boy. These aren’t just conceptual ideas in the story, but have a physical impact upon the characters. As is vital in the best absurdist fiction, these weird details are treated in the narratives as completely natural so the meaning of their inclusion adds a forceful complicated layer to the progression of the unfurling story. The diversity of love is demonstrated in different stories involving romance that is lesbian, gay, straight and in-between. Female sexuality in particular is assiduously explored over a range of stories. The story ‘Momma Grows a Diamond’ is one of the most beautifully crafted stories about a girl’s coming of age that I’ve ever read. Girls are initially given the names of flowers, but as they blossom into adulthood they take on the names of jewels. Logan writes at one point: “Aren’t you tired of being a flower, Violet? Momma says to me one morning from the depths of her bed. Flowers crush so easy, baby, but nothing breaks a jewel.” This description of a necessary toughening of character in women is a meaningful and different way to see how personalities change with adulthood out of a need to deal with a new kind of social environment. There is also a particular kind of masculine aggression ingeniously represented in the story ‘The Broken West.” I’ve heard it said before that when two men look each other in the eyes they only ever think one of two things ‘I want to fuck you’ or ‘I want to kill you.’ This idea is demonstrated in the line “Daniel can’t tell if he’s been fighting or fucking, and it doesn’t really matter. Faces look different close up, and the only way to get that close to a stranger is to kiss them or choke them.” These stories cleverly play with gender to show how it sometimes determines or heedlessly defies the ways in which sex plays out or how love manifests.

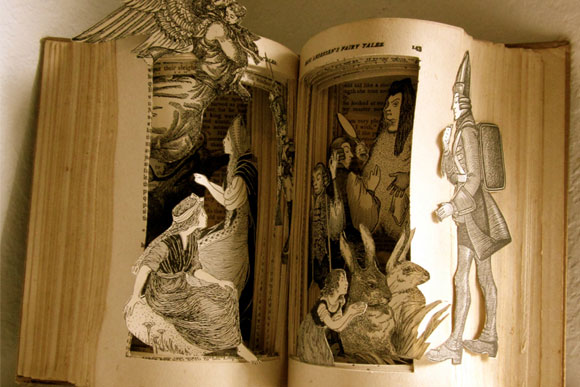

An Altered Book: Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen - by artist Susan Hoerth

Logan also displays a diverse range of narrative techniques throughout so that some stories are told in short bursts of revolving first person narration while others like ‘Tiger Palace’ has a commanding narrator who leads you manipulatively through the tale and makes you question the meaning of “stories” themselves. Some tales are whimsical and retain elusive meanings. Others are slotted more firmly in particular kinds of genre, but draw into them innovative subject matter. In the haunting, melancholy story ‘Feeding’ a man prepares a nursery while his female partner becomes increasingly obsessed with tending to her garden at night. The creepy tone and continuous image of a trowel hitting dirt makes this story as eerily tense as any psychologically-rich horror story. In a completely different style the story ‘The Man From the Circus’ uses a girl’s newfound profession as a trapeze artist as a significant metaphor for taking a necessary chance in life by plunging dangerously into the unknown world.

As you can tell from my enthusiastic attempt to untangle the meaning of these stories, despite their relative brevity they contain a wealth of ideas. Kirsty Logan is very clever in the way she uses a range of writer’s tools to create the most effect style of storytelling to fit the diverse subject matters she covers. Having been a teenage lover of absurdist drama, I'm thrilled by the way she warps reality in her prose to stimulate the imagination. She crafts disarming images that are imbued with unusual meaning. “The Rental Heart and Other Stories” is a fantastically refreshing read and leaves you thinking about things in a new way. These stories have picked up awards and been included on prize lists both individually and as a collection itself which is a testament to their good quality.

Watch a video of Kirsty Logan discussing the nature of fairytales here: http://vimeo.com/104486851