It’s really exciting seeing the international book community experiencing a surge of interest in Latvian literature. I’m aware that there is a vibrant literary scene in Latvia, but translations of new Latvian fiction are slow in making their way to the West. So I was thrilled to read “Soviet Milk” by established author Nora Ikstena. This book won the Annual Latvian Literature Award in 2015, but has only just been translated and published in English. The story alternates between the perspectives of an unnamed mother and daughter over a number of years from 1969 to 1989. They have a tumultuous relationship with each other and both struggle to find their place in society because this was a period of time when Latvia was still under Soviet rule. The mother is a skilled doctor specializing in female fertility, but finds life in the communist system stiflingly oppressive. Equally the daughter struggles to grow and nurture her developing intellect in such a regimental system. This is a moving and achingly poignant story of an unconventional mother-daughter relationship and a country undergoing radical social change as Latvia regains its independence.

At first the mother and daughter’s sections are separated by years of time as the mother describes her childhood and the very different landscape of Latvia during WWII. Meanwhile the daughter describes the painful experience of feeling unwanted and being raised by her grandmother and step-grandfather because her mother is incapable of caring for her. Gradually their narratives come together until they occur in a simultaneous time period. It’s ironic that the mother specializes in reproduction, yet finds no motivation to mother her own daughter. She feels “I had carried and given birth to a child, but I had no maternal instincts. Something had excluded me from this mystery, which I wanted to investigate to the very core, to discover its true nature.”

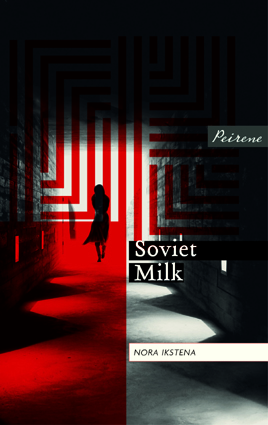

Nora Ikstena

In some ways it feels like the mother can’t nurture her daughter because she can’t inhabit a fully rounded identity under the Soviet system. She’s an intellectual who hordes works of literature that have been banned and experiences severe mental health problems. The daughter is equally intelligent and as she grows discovers how her curiosity is equally curtailed by a regime that seeks to instil only a Soviet-approved point of view. People who don’t fit into the system such as a brave poet who tries to teach school children an alternative point of view or the mother’s friend Jesse who might be intersex or transgendered are winnowed out.

The novel filters such a rich view of Latvian history through three generations of characters. Although we only get the perspectives of the mother and daughter, we’re also given snippets of the grandparents’ points of view. Having lived through so much oppression the step-grandfather resignedly feels: “one shouldn’t dwell on the past. Nothing would change here. The Russian boot would be here for ever.” However, as the daughter comes of age she becomes aware that a new age is finally coming where Latvia can achieve independence from Russia once again. Nevertheless, there are potent and ever-present reminders of the severe violence and tragedies that the Latvian people experienced. Even in a field of growing crops it’s remarked how “Cabbages, beetroot and potatoes to provide for our Soviet pigs would grow abundantly here, for bodies from military executions fertilized the soil.” There is a striking sense of progression within the novel where the physical bodies of the people and their stories persist through succeeding generations. It illuminates the distinct personalities of certain characters in how the weight of history impacts them, but also shows a cumulative sense of national identity.

Interview with Nora Ikstena

Eric:

I greatly enjoyed reading this novel - particularly because I have Latvian heritage and distant Latvian relations, but I know little about this part of my family’s history. The story poignantly focuses on different generations of Latvian life, history and social change. What was your initial inspiration for the novel?

Nora:

In 1998, I wrote my first novel Celebration of Life. It tells the story about the daughter going to her mother’s funeral after not knowing her mother all of her life. I got the first copy of my novel on the day of my own mother’s funeral. That was also the day when I started to think of Soviet Milk. It took 20 years. It’s my most important novel, as it's very personal for me. It's a real story about a mother's and daughter's complicated life under the Soviet regime in Latvia 1969-1989. It’s near to autobiographical, but I think this is honest to share your own life experience with readers. It was important for me to tell this story not only for readers in Latvia but also across borders.

Eric:

Milk takes on many complex metaphorical meanings where it isn’t always something nutritional or life-giving, but which might also be tainted or bitter. How did the image of milk as a symbol evolve for you while writing?

Nora:

Milk, especially mother’s milk, is an essential liquid of life. In my novels it becomes poisoned milk because the mother does not want to give it to her daughter. She does not wish the same life in a cage for her daughter, as she has. At the same time it is a metaphor – poisoned milk of our homeland, for what we were drinking during the Soviet occupation. It is also very poetical – in Latvian folk songs called ‘dainas’ we have many sayings about milk. For example – water is warm like milk, or ‘milk rivers’ or Milky Way in universe. It is all went together in my novel.

Eric:

I found it fascinating how traditional family roles are somewhat subverted in the story where the daughter often takes on a mothering role. This subversion is emphasised by the fact we never learn the characters’ names so it’s as if they are locked in these identity roles which don’t accurately suit them. Did you always plan to leave the central characters in the novel unnamed?

Nora:

No, that is first time in my writing I leave central characters unnamed. And I did it on purpose. I wanted to generalize the story. The story is inspired by my life, but it’s also a story about anyone who has experienced love and loss, and that battle of trying to bring someone back to life. These people in search of the truth, who in the process struggle against the everyday life, its troubles and joys, and the reversals of fortune. It's a story about a cage and freedom, about endless love, and about life that is larger than literature.

Eric:

The mother’s friend Jesse is such a compelling character who takes on a kind of family role as she has been rejected by her own family and peers. What inspired this story line of someone who is intersex or has gender confusion?

Nora:

Jese comes from my favourite Christmas song – I know the beautiful rose that blossomed from the heart of Jese. For my mind Jese is a symbol of unconditional love. Spiritual love. Somebody in between man and woman, soul and flesh. Jese is true and devoted. Pure love.

Eric:

Some classic novels of Western literature such as Moby Dick and 1984 are referenced throughout the novel as subversive books read in secret. Do you know of many instances of forbidden literature being secretly shared while Latvia was under Soviet rule?

Nora:

There were many instances of forbidden literature, because the role of literature in Latvia is enormous. We are nation of readers. It has been like this all the historical times (and I am sure will be in future.) I can give an examples of two translations: 1984 by Orvell and Ulysses by Joyce into Latvian. Both were translated by Latvian exile translators and published in 1950s by the Latvian exile publishing house in Sweden. Then some copies were secretly passed to Soviet Latvia. For many intellectuals these underground copies were like a Bible at that time. Imagine that you can have a copy of Ulysses for three reading days? People went to jail for reading such a book. At the same time our national poetry was a huge part of Latvian expression during the Soviet rule – with hidden and obscure meanings, it offered a subversive insight and poets were at the heart of this subversive expression, and thousands of people would come together in the street to hear their voice.

Eric:

It feels as if each of the three generations represented in the novel aren’t entirely aware of the many social and political challenges faced by previous generations. Do you feel children in Latvia today are more aware of the complex history their elders lived through?

Nora:

Literature plays an in important role in Latvia, particularly in the way it allows us to share our history through a personal perspective. There is a new series in Latvia called ‘WE.XX Century’ which explores different aspects of our history through 13 novels. These are all best sellers – with the old and the young – as fiction is such a powerful way of communicating our past and our country, which has forged its independence in the beginning of it and lived through the horror of two world wars, followed by Soviet era, and dramatic regaining of independence.

Soviet Milk is published in the UK by Peirene Press, translated from the Latvian by Margita Gailitis. The Baltic countries – Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania – will be the Market Focus for the London Book Fair 2018 (10th – 12th April). Nora Ikstena is the Latvian ‘Author of the Day’