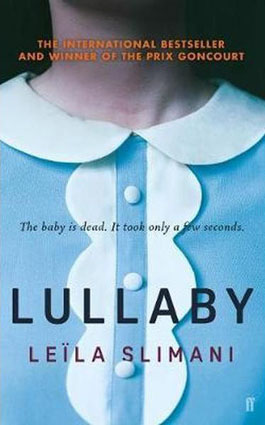

One of last year’s biggest literary breakouts was Leila Slimani’s Prix Goncourt winning novel “Lullaby” (known in the US as “The Perfect Nanny”). Her novel “Adele” was published in France before “Lullaby”, but it’s only now been translated and published in English. The heroine of this novel’s title is a journalist and mother with a steady husband. She appears normal and content, but running parallel to this stable life she has a secret existence filled with unruly passion and illicit affairs. She lazily does her job and barely musters the energy to get to the office every day. She resents her child and is turned off by her husband. All her passion is poured into furtive moments where men unleash their desire upon her because “Her only ambition is to be wanted.” This seemingly chaotic double life is untenable and there must be a breaking point.

Even though Adele’s case is extreme, her story is extremely relatable for the way we all harbour secret passions that we keep carefully concealed from those closest to us. She frequently resolves to turn her life around and devote more time to her husband and son, but finds herself drawn back into seedy behaviour because “Her obsessions devour her. She is helpless to stop them.” I admire how the psychological motivations for her behaviour are never neatly explained and there’s no clear-cut course of action or treatment to “solve” her habits. Instead, the novel shifts at one point to include the husband’s perspective more and shows how he has psychological hang ups as well which are preventing full intimacy and disclosure between them.

While it may not have the depth and poeticism of a novel like Garth Greenwell’s “What Belongs to You” which similarly explores the dynamics of someone driven by desire, I appreciated Slimani’s frankness in showing how eroticism can come to rule someone’s life. Adele isn’t driven by pleasure so much as a confrontation with mortality and a submission to the mechanisms of the body. This novel is a vivid study of how sometimes the relationships which are meant to support us are the ones which can lead to the annihilation of our innermost selves.