When I was young the mother of one of my best friends suffered badly from mental illness. It was a hardship he mainly bore in silence, but sometimes the disturbance it caused to their family life spilled out into the open. I witnessed the shame this caused him. The evident love the family held was twisted and broken by frustration. I saw the aggravation it caused her not being able to be the mother she wanted to be, but there was nothing she could do to prevent the terrors from plaguing her mind. We tried to accustom ourselves to what we knew was not normal, but, being young, it’s not easy to empathize with hardships you don’t understand or appreciate what makes people unique. So I felt a real connection reading this novel about a mother struggling with mental illness and her family’s struggle to help her.

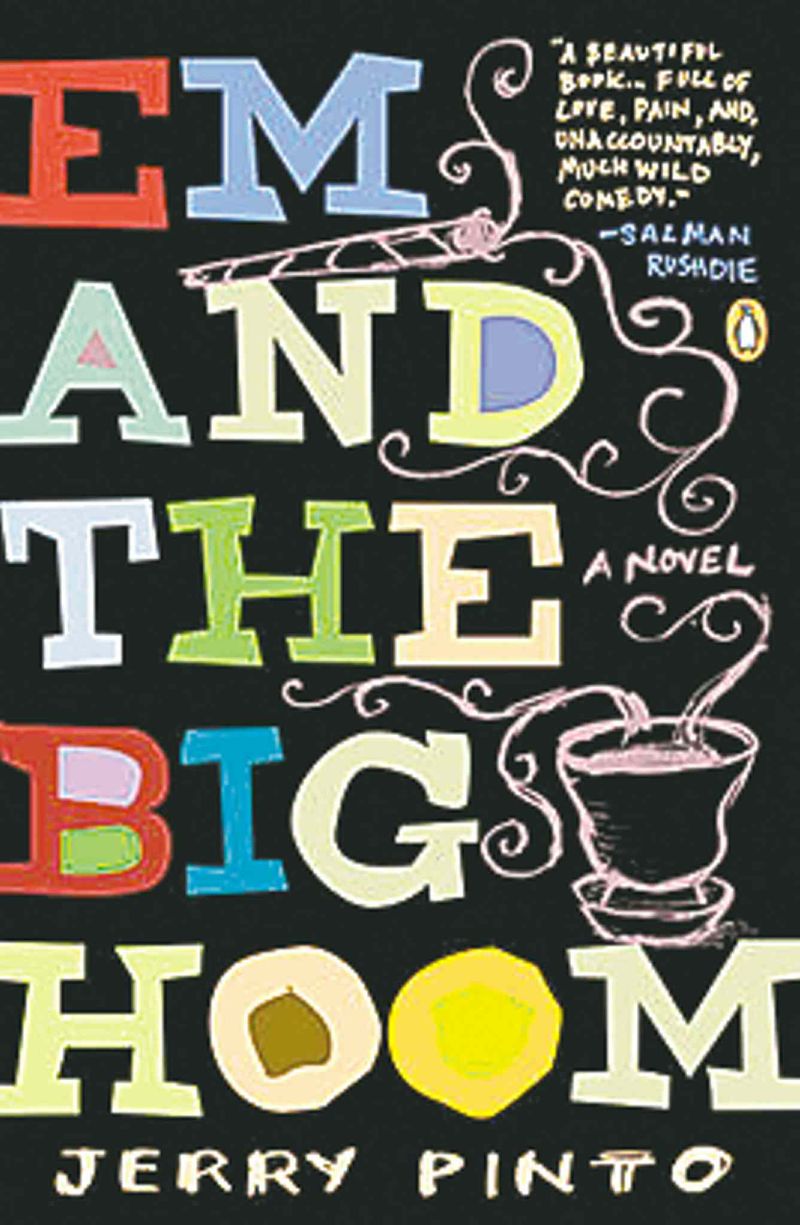

How do you cope when a family member has a mental illness? For people who have a loved one that suffers from this disability, in whatever form it takes, they know the heartache caused by having their love tested year after year. The cold hard truth is that as Jerry Pinto writes in this novel: “Love is never enough. Madness is enough. It is complete, sufficient unto itself.” This is the experience represented so movingly and astutely in “Em and the Big Hoom.” It’s important to remember that for all the frustration, embarrassment and agony which can accompany caring for someone who is stricken by a mental disease there are also occasional moments of true happiness, humour and inspiration. This book is no romantic portrait. Rather, it's an inventively told story of a family who battle for years to save the mother from the ravages of her illness.

The narrator tells the tale of his family and his mother's disability in fragments. Most of the story is composed of dialogue between the narrator, his sister and mother, Em. They don't have the kinds of conversations you'd normally expect a mother to have with her teenage children. She is disarmingly confessional, flagrantly sexual and speaks with mysterious turns of phrase. Meanwhile, the father, nicknamed “The Big Hoom,” is the pragmatic voice of reason in the family. The narrator's account moves back and forth in time, occasionally reproducing selected letters or diary entries. The family's history builds slowly out of these fragments which recall the parents' courtship, Em's employment, early years of motherhood and her slide towards increasingly manic behaviour. I think the reason Pinto chose to unfurl the story in this piecemeal structure rather than giving a linear narrative is that no straightforward way of telling is appropriate for the experience. The narrator describes how “Conversations with Em could be like wandering in a town you had never seen before, where every path you took might change course midway and take you with it.” The narrative style reflects this. Em's story can't be neatly summed up because it would betray the confusion that remains for the narrator about his mother's life. Although he grew accustomed to the way her mental illness affected her behaviour, she remained a mystery to him – one he desperately wants to solve.

Excellent interview between Jerry Pinto and Madhu Trehan about the novel and writing

Em is a fantastically compelling character for the reader as well. She speaks to her children about sex. When discussing dates she comments that she doesn't see the point of a goodnight kiss because “why send the poor man off with a hard on? Unless you’re a tease.” She makes blunt comments which can be very insightful and funny such as “I don’t understand Zen. It seems if you don’t answer properly, or you’re rude, people get enlightened.” Other times her paranoia and mania rises to the point where she’s mercilessly cruel about her own children to their faces, expressing her hatred of becoming a mother: “I didn’t want to have my world shifted so that I was no longer the centre of it. This is what you have to be careful about, Lao-Tsu. It never happens to men. They just sow the seed and hand out the cigars when you’ve pushed a football through your vadge. For the next hundred years of your life you’re stuck with being someone whose definition isn’t even herself. You’re now someone’s mudd-dha!” This blunt honesty would be startling to hear in itself, but for her to be saying it to her own children is shocking. Of course, there are threads of honesty in it which are feelings probably common to many people. I don’t want to make crass statements about how the mad are not really mad or have special insights that those who are conventionally considered sane do not. What I think is important to consider is that people can’t be simply dismissed as mentally ill, but that there are external factors which those who are prone to mental illness can be particularly sensitive to and effected by.

This novel shows what the repercussions are for the narrator who cares for his mother and how his own identity is limited because he can’t have a life outside being her carer. His struggle with his own dark feelings is meaningfully conveyed. It also shows what strength and love the family has to stick by her. Some people are abandoned as in one scene in a mental institution when a warden remarks “This is a hospital but it is also used as a dumping ground, a human dumping ground.” It’s tragic to think of people’s mental health conditions exasperated by being left alone and that even if a recovery is made there is no home to go to. It’s all the more painful wondering if you’d have the spiritual strength to stick by loved ones who fall victim to conditions of mental illness. “Em and the Big Hoom” is a really powerful novel that challenges your assumptions.