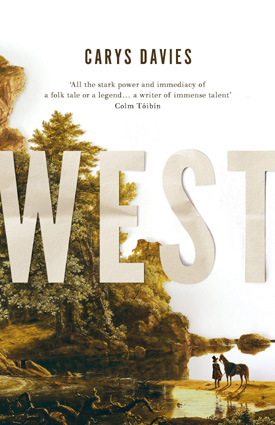

It’s interesting when book prizes such as the Rathbones Folio Prize consider contenders from very different genres and styles. This year’s shortlist places nonfiction alongside poetry and fiction. But even the nominated fiction including Burns’ highly stylized “Milkman” and the contemporary “Ordinary People” varies wildly. Most striking are the lengths of the two historical novels in contention: “Mary Ann Sate, Imbecile” by Alice Jolly which is 640 pages and “West” by Carys Davies which is a mere 149 pages. In a way it feels impossible that these books can be judged against each other, but since they have included such a diverse list I assume the judges must only be considering the excellence of the book itself and how well they believe the authors succeeded within the parameters of form. In this way, “West” excels in how it tells a straightforward, succinct and simple story that has a much bigger meaning.

In early 19th century America a widower named Cy Bellman journeys out to the wild west leaving behind his adolescent daughter Bess. He’s seen a news report that the bones of colossal unknown beasts were discovered there so he sets out hoping to discover if any of these rare animals survive. His mission is undoubtably foolish as such a dangerous journey at this time takes years and means he has to entrust the business of his farm and the raising of his daughter to his sister Julie. It’s not even an endeavour to strike it rich like in a gold rush, but just to witness a heretofore unknown creature of enormous size. We follow the years of his hazardous journey alongside the perils his daughter Bess faces as she grows into womanhood. It’s utterly gripping and poignantly told.

It’s a complicated task to portray a male character who acts with such arrogance and stubborn pride. In a way I hated Cy for abandoning his responsibilities to his daughter and leaving a life where he could have been quite content. He even had the prospect of a new romance with a local woman who was a widow. But at the same time he was merely asserting his independence to pursue his dream (even if he was only acting on what today would be considered a mid-life crisis.) It’s a radical act in response to the weight of responsibility he feels and his unresolved grief at the loss of Bess’ mother. Clearly Cy wasn’t doing what was morally or logically right, but Davies effectively shows the complexity of his decision.

It can be tricky for an author to portray a man acting selfishly and at the expense of others in a sympathetic way – as I felt when reading the recently translated novel The Pine Islands. These novels have another interesting parallel of having non-white “sidekick” characters whose dilemmas are taken seriously while not being treated with equal weight to the primary white male character. Cy enlists the help of a Native American Shawnee teenage boy named ‘Old Woman From a Distance’ to help guide him. His tribulations are treated seriously and in a way I felt he was the most complex character in this novella. But Davies portrays all her characters in a way which maintains their integrity and highlights their sometimes horrific actions while not placing any judgements on them.

Aside from these characters’ personal stories this novella seems to be saying something much bigger about the country as a whole and the human impulse to chase illusions. In America’s mission to expand and grow it paved over the land’s history and decimated the native people who inhabited it. The novel shows the casualties of this and the innate desire some people felt to connect with this forgotten history. At the same time it shows how pursing what seems most foolish can become the most important drive in an individual’s life. The novella opens up a lot of issues which leave subtle questions in the reader’s mind and I admired how it does all this with tremendous economy.