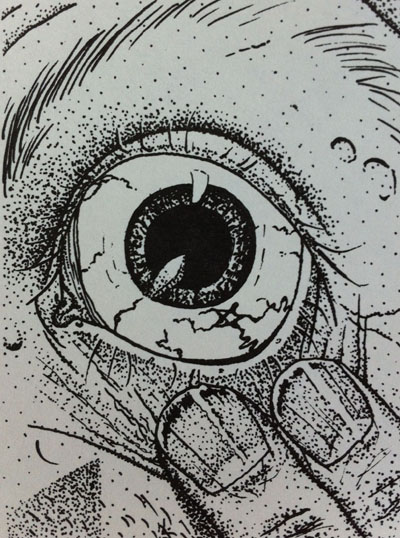

In her introduction to the anthology American Gothic Tales (1996) which Joyce Carol Oates edited she pays tributes to the gothic tradition in American literature bourn out of a crisis in the Puritan consciousness. She detailed how writers such as Washington Irving, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, Charlotte Perkins Gilman and H.P. Lovecraft wrote unsettling fiction in which “the ‘supernatural’ and the malevolent ‘unconscious’ have fused” and how Lovecraft, in particular, has a compulsion in his fiction “to approach the horror that is a lurid twin of one’s self, or that very self seen in an unsuspected mirror.” Such a crisis in consciousness where the real and unreal intermingle to produce horrific results is adeptly-realized in the six unsettling and mesmerizing tales contained in Oates’ new book The Doll Master and Other Tales of Terror.

Reading about characters such as a lonely boy whose sister died of a rare disease, a diligent adolescent girl entrusted with house-sitting a beloved teacher’s upscale residence or a wife who ardently desires to be a loving companion to her charismatic husband, we want to believe and trust these sympathetic individuals. Even when taken into the point of view of a white man imprisoned for shooting dead an unarmed black boy, we guardedly hope that there has simply been a misunderstanding as he so vehemently insists. We do this in order to preserve our belief in people’s essential “innocence” and “goodness”. We’re invited in these stories to connect with these characters’ experiences - sometimes in a bracingly direct manner such as this passage in the title story: “All your life, you yearn to return to what has been. You yearn to return to those you have lost. You will do terrible things to return, which no one else can understand.” The involved reader will hesitantly survey his own emotionally conflicted experience as well as fearfully wondering what lengths the cryptic narrator has gone to assuage his own painful feelings about his past. Here is the perverse pleasure of these stories which become so personally involving it’s as if we see the horrific consequences created from our own darkest compulsions (albeit within the “safe” realm of fiction).

Oates has a masterful way of leading us through the consciousness of the troubled individuals at the centre of these stories so that heartfelt sympathy is gradually replaced by guarded unease and, eventually, by a terrifying repulsion. Paranoia leads the characters to conclusions which make them act in a way to justify reprehensible actions. Their fear often comes from social issues such as drug abuse, economic inequality, racial divisions or child kidnapping. The narrator of the story ‘Soldier’ remarks how “Uncle T. has told me This country is at war. But it is not a war that is declared and so we can't protect ourselves against our enemies.” Destructive divisions are created by ideological notions passed down by political rhetoric, extreme religious institutions or inflammatory media sources to create an “us” and “them” mentality where the characters feel drawn into taking extreme action to defend against insidious encroaching forces. At other times, paranoia arises in a more domestic setting from problems that seem sadly endemic of the human condition like a fear that those we love will eventually betray us.

Many stories contain surprising and satisfying twists worthy of the most compulsively-readable tales of Poe or Agatha Christie. Unexpectedly the hunter might become the hunted. Those who seemed well-meaning or benign become frightfully sinister. What felt like sure fact turns out to be fiction formed in a character’s deluded mind. Oates finds inventive methods for keeping the reader on their toes. She invokes the methods of this genre’s great masters while building upon them with issues current to today. “Mystery, Inc” pays the most playful tribute to the suspense genre as it is set in a rural bookstore which contains enticing treasured editions from some of America’s greatest writers. It also allows Oates to engage with a meditation upon the genre itself as a touchstone for our most personal philosophical concerns. The shop’s gregarious owner states that “It is out of the profound mystery of life that ‘mystery books’ arise. And, in turn, ‘mystery books’ allow us to see the mystery of life more clearly, from perspectives not our own.”

"the lonely Siamese cat appeared in the kitchen doorway staring at me with icy blue eyes" from 'Gun Accident: An Investigation'

Another story 'Big Momma' has the tenderly emotional and creeping sinister feel of a fairy tale. An insecure middle school student named Violet who has recently moved with her working single mother to a new area ingratiates herself with a welcoming close-knit family run by a single father. She’s rebellious against her mother and seduced by the caring affection of her friend’s father. Although she becomes naturally wary of something unsettling about her new adopted family, she is seduced by the acceptance she finds with them which feeds her emotionally and physically. The startling outcome and imagery invoked by this parable of young adulthood produces a distinctly haunting feeling.

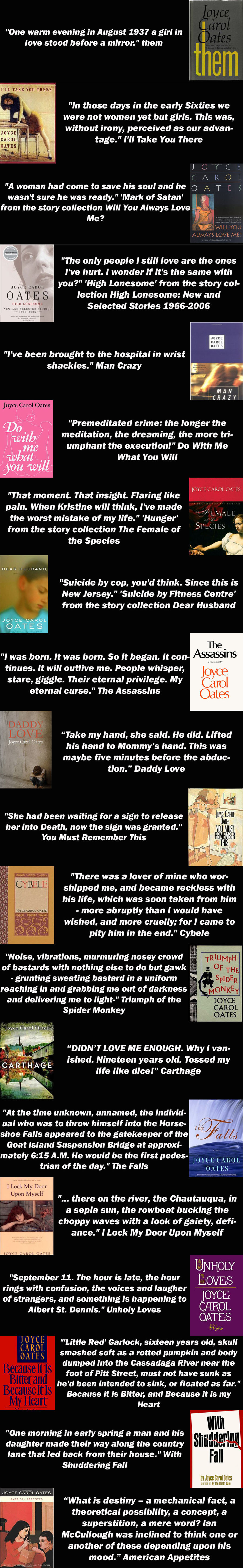

Oates has previously invoked elements of genre fiction in multiple novels and story collections. These range from novels of ambitious literary scope such as her gothic quintet of books which she first began publishing in the early 80s with the family saga Bellefleur (1980) and only recently completed with the historical gothic-horror novel The Accursed (2013). Some story collections approach genre in a more straightforward manner such as her books Haunted (1994) and The Collector of Hearts (1998) which indulge in sinister stories of the “Grotesque”. Last year she produced Jack of Spades: A Tale of Suspense (2015) which takes the form of a thrilling story about author-rivalry and pseudonyms. With The Doll-Master and Other Tales of Terror, Oates has created unique, gripping stories which take us to the most extreme edges of what people are capable of when logic breaks down and their minds are plagued by virulent emotions. The terror comes from knowing that with a twist of fate their stories could become our own.

This review also appeared on Bearing Witness: Joyce Carol Oates Studies