This year’s Man Booker Prize shortlist is a really interesting and challenging group of novels. I’ve been particularly busy in the last few weeks but I have managed to read five out of the six books listed. I was totally engrossed by the twisted psychology and suspenseful plot of Ottessa Moshfegh’s “Eileen” and fascinated by the compelling portrait of manhood David Szalay created in his nine distinct stories about men’s lives in “All That Man Is”. Paul Beatty's "The Sellout" is an extraordinary satire that fearlessly, hilariously and cleverly gives a new perspective on racism in America. But I have to say, two of my favourite books I’ve read so far this year are Deborah Levy’s “Hot Milk” and Madeleine Thien’s “Do Not Say We Have Nothing”. Levy’s novel takes a brilliantly unique look at identity, family and sexuality. Thien’s novel is a complex, sophisticated story showing generations that struggle for personal freedom and creative expression. It’s difficult to choose, but I’m going to guess that “Do Not Say We Have Nothing” will win. I’ve even placed a bet at the bookies for it to win! I successfully predicted that “A Brief History of Seven Killings” would win the Booker last year so I’m hoping to collect this time as well when the winner is announced on the evening of Tuesday, October 25th! More excitingly, it will be great to follow all the bookish discussion around these compelling books that have been shortlisted.

David Szalay has found an inventive way to portray the hearts and minds of men in this novel which follows nine distinct characters at certain points in their lives. From young aesthete/wallflower Simon who travels around Europe to savvy journalist Kristian on the brink of publishing a sensational piece about a high profile affair to elderly Tony who resides in Italy mulling over unexpressed desires with his adult daughter, the parts of this novel progress through stages in different men’s lives alighting upon commonalities and variations of experience. It felt to me like each part or short story could have been easily expanded into a novel in itself, but paired together they make a fascinating composite portrait which questions ideas about masculinity and life’s meaning. Towards the end especially, “All That Man Is” feels something like a Beckett play where the men’s common yearnings and regrets have accumulated together to sound like one voice crying out for all human experience.

Through several of the men’s stories there is a marked disconnect between how these characters confidently portray themselves publicly and the feelings of self-doubt they harbour privately. Szalay skilfully moves his narrative between these two spheres of experience to show dramatic points where the self-assured mask a man might wear crumbles. This sometimes happens in instances where an arrogant man is undone by desire like in the story of young slacker Bernard who finds himself seduced by both a mother and her daughter while on holiday in Cyprus. Or when social outcast Murray finds himself emotionally moved by a psychic who he nonetheless realizes must be a con-artist. Through this it is shown how men are compelled to maintain confident fronts both because of societal pressure to appear strong, but also out of an oftentimes unjustified personal pride.

As the novel progresses and the male protagonist of each new story become older there is an accumulating sense of the flow of time: how these men’s lives are caught up in details and misadventures which distract from their ideals and larger goals. Many of the younger men don’t give too much thought to this caught in their own admittedly false sense of their immortality: “this too shall pass. We don’t actually believe that, though, do we? We are unable to believe that our own world will pass.” The stories in the middle of the book are concerned mostly with professionals who are embroiled in the busyness of their professional ambitions and work life: “Life has become so dense, these last years. There is so much happening. Thing after thing. So little space. In the thick of life now. Too near to see it.” Their unquenchable drive for power, money and status leave them little time for reflection or valuing things which should matter more like caring for their family or maintaining a sense of integrity. This takes on a poignancy with the later stories where the men often feel they’ve not achieved what they really wanted and have little drive to continue. This is most touchingly realized in the story of wealthy iron baron Aleksandr who is living through the collapse of his mighty empire and seeks a little feeling of home with an employee.

Frenchman Bernard goes on a cringe-worthy cheap holiday to avoid any responsibilities

This book raised a lot of questions for me and gave me many conflicted feelings. I love how it exposes and satirizes how petty, selfish and short-sighted men can be which makes the reader question the idea of masculinity. But, at the same time, I kept thinking about the title and wondering ‘is this really all man is?’ There is little of the subtly about men which is so finely articulated in Andrew McMillan’s superb book of poetry “Physical”. Of course, the nine men in this novel certainly don’t represent all of mankind, nor do I think Szalay intends them to. Although there are some positive and humorous qualities about some of the men portrayed - with Balazs and Tony in particular demonstrating a sensitive side - they are overall quite nasty. Men can also be caring, compassionate and giving, but I think Szalay was more interested in exposing specific types of men and the inner lives they hide. It also shows how certain men perceive women and how women must navigate this male gaze. He does this in an accomplished way and its impressive how instantly I felt immersed in each part even though it was about an entirely new character in a different situation disconnected from all those before it (except for the final part).

“All That Man Is” is ultimately a fascinating and thought-provoking novel that leaves a lasting impressing.

The narrator of "Eileen" is so painfully introverted and isolated in her thoughts I felt instantly on edge and utterly compelled by her story. As a now elderly woman, Eileen recounts a week in her life back in 1964 when she was a young woman who lived a very claustrophobic life with her alcoholic widower father. At that time she was friendless, worked in a correctional facility for young offenders and spent her free time on booze runs for her father or in the attic reading issues of National Geographic. Although she was secretly plotting to run away from her small New England town, the arrival of an attractive new staff member named Rebecca creates a dynamic tension that changes everything. Filled with squeamish descriptions of Eileen’s extremely self conscious physical and mental state, this sinister novel builds to a dramatic conclusion

The narrator of this novel reminded me slightly of “The Looking-Glass Sisters” because she’s so overwhelmingly uncomfortable in her own skin and lives in an isolated damaged household. Eileen is so acutely embarrassed by her own physical being that she even states “Having to breathe was an embarrassment in itself.” She has a heightened awareness of the smells and functions of her body. With so much disdain for her own being it’s no wonder she doesn’t have the self confidence to make any friends, let alone find a relationship. She has a romantic obsession for a man and frequently lingers outside his house. Eileen is equally critical and vile about other people as she is about herself. The comments she makes about her colleagues are frequently vicious and perverse. In an understated way she claims: “Looking back I’d say I was barely civilised. There was a reason I worked at the prison, after all. I wasn’t exactly a pleasant person.”

The only close relationship she has is with her father a man who drinks copious amounts of gin each day, protectively clings to his gun from his days in the police force and treats Eileen with abominable disdain. Eileen came back to live with him when her mother grew gravely ill, but since her mother’s death continued to stay with him far longer than she should have. Her beautiful and more confident sister Joanie left quite some time ago. Eileen skulks through life hiding her emotional state behind what she terms her “death mask” and flails about within her twisted fantasies. Throughout the novel I felt we were meant to question how truthful Eileen is being with the reader because it’s about a period in her life so far in the past. Also, she’s quite cagey with certain details. For instance, she never names this town of her youth referring to it cryptically as X-ville.

Frequently there are descriptions of the threat of icicles hanging from the roof of the house which Eileen imagines killing her or her father.

Eileen is so determinedly unlikeable that she’s actually quite fun to read about. I enjoyed her indulgent descriptions of repulsion for almost everything and everyone around her. It’s quite fun reading about someone living so firmly within her own rules that she shoplifts, creates teasing questionnaires for the mothers of the imprisoned delinquents and engages in other antisocial behaviour. Sometimes she’s flat out bitchy like in her judgement of one woman where she states “Her lipstick was a cheap insincere fuchsia.” In her disdain for the human condition she also explores a dark side of humanity from a highly unique angle. For instance, she feels that “Violence was just another function of the body, no less unusual than sweating or vomiting. It sat on the same shelf as sexual intercourse. The two got mixed up quite often, it seemed.” Anyone from the outside looking in on her situation would probably disagree and understand how a toxic situation has created a very damaged individual. But these strident opinions and alarming situations feel quite natural for Eileen because it’s all she’s known.

Hovering in the background is the knowledge that something very sinister has occurred, but the reader doesn’t fully understand the situation until towards the end of the novel. I enjoyed how Ottessa Moshfegh builds this tension with creepy descriptions and teasing passages which gradually build up an alarming amount of dread. Eileen is someone who only lives by her own moral code and it’s alarming to discover from her that “I didn’t believe in heaven, but I did believe in hell.” The consequences of her particular belief system create an atmosphere of tension which makes for compulsive reading. “Eileen” is a wickedly unsettling and mesmerising novel.

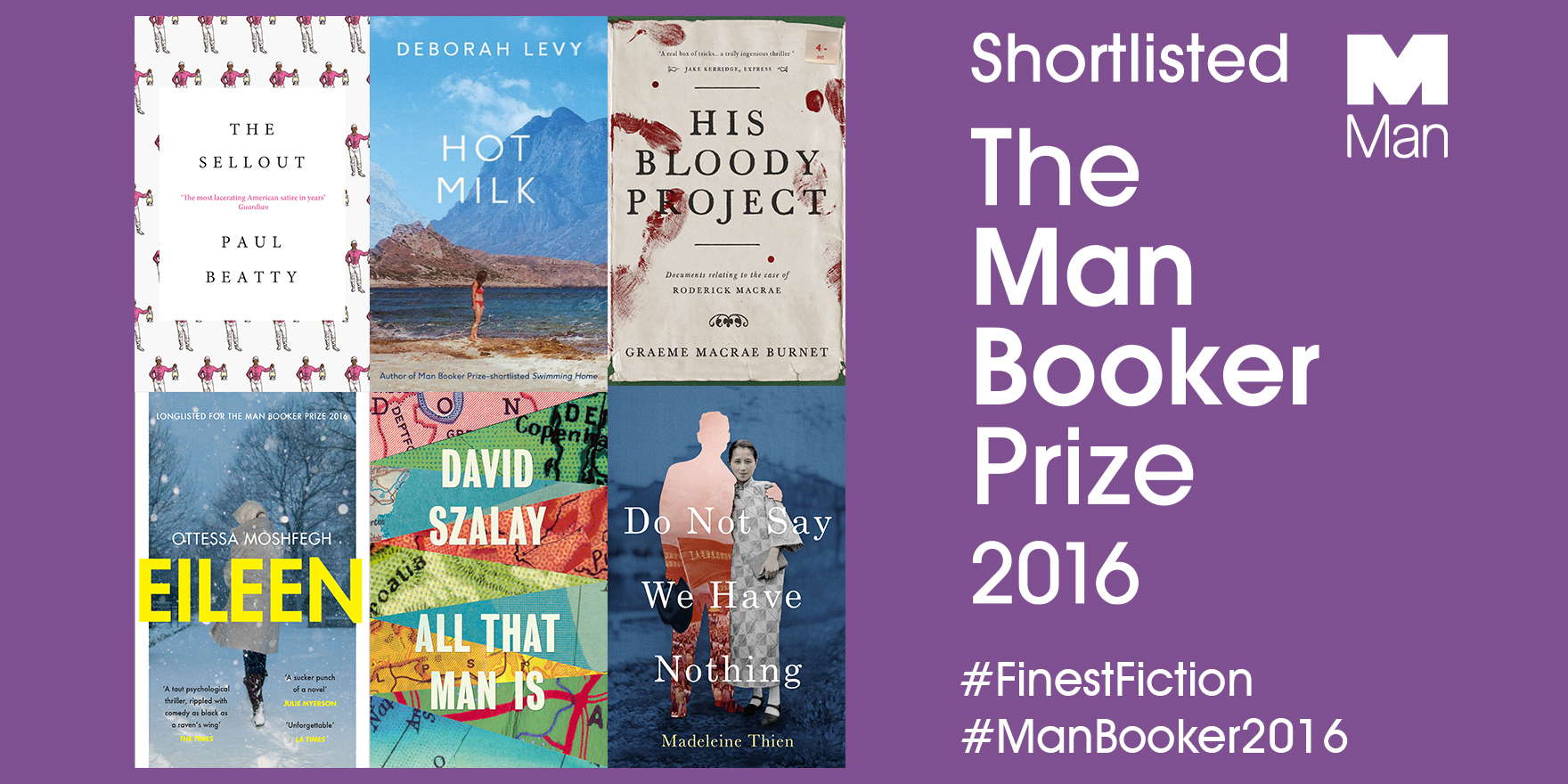

After much speculation and excitement, the shortlist for the Man Booker Prize 2016 has been announced! I only managed to guess three out of six and I’ve only read two of these. But I am so thrilled that Deborah Levy’s “Hot Milk” and Madeleine Thien’s “Do Not Say We Have Nothing” are on the list. These are two of my favourite new novels that I’ve read this year and really deserve to be read by a wide audience. However, I’m equally excited to see Paul Beatty’s “The Sellout”, David Szalay’s “All That Man Is”, Graeme Macrae Burnet’s “His Bloody Project” and Ottessa Moshfegh’s “Eileen” on the list as I’ve been eager to read all four of these.

The chair of judges, Amanda Foreman commented: ‘The Man Booker Prize subjects novels to a level of scrutiny that few books can survive. In re-reading our incredibly diverse and challenging longlist, it was both agonizing and exhilarating to be confronted by the sheer power of the writing. As a group we were excited by the willingness of so many authors to take risks with language and form. The final six reflect the centrality of the novel in modern culture – in its ability to champion the unconventional, to explore the unfamiliar, and to tackle difficult subjects.’

The novels have a real mixture of subject matter and styles. From the jellyfish laden beaches of Spain to 1960s New England to musicians in Mao’s China to a race trial at the US supreme court to murders in 19th century Highlands to a pan-European look into the lives of men. It’s great to see a gender balance and diverse list of authors as well. There are two British, two US and two Canadian writers on the list. I’m eager to delve in and get debating about who the winner should be. The winner will be announced on October 25th. Are you eager to read any on the list? Who do you hope will win?